WALL STREET AND THE

BOLSHEVIK REVOLUTION

By Antony C. Sutton

Chapter V

THE AMERICAN RED CROSS

MISSION IN RUSSIA

1917

Poor Mr. Billings believed he was in charge of a scientific mission for the relief of

Russia .... He was in reality nothing but a mask — the Red Cross complexion of the

mission was nothing but a mask.

Cornelius Kelleher, assistant

to William Boyce Thompson

(in George F. Kennan,

Russia

Leaves the War)

The Wall Street project in Russia in 1917 used the Red Cross Mission as its operational vehicle. Both

Guaranty Trust and National City Bank had representatives in Russia at the time of the revolution.

Frederick M. Corse of the National City Bank branch in Petrograd was attached to the American Red

Cross Mission, of which a great deal will be said later. Guaranty Trust was represented by Henry Crosby

Emery. Emery was temporarily held by the Germans in 1918 and then moved on to represent Guaranty

Trust 'in China.

Miss Mabel Boardman

Up to about 1915 the most influential person in the American Red Cross National Headquarters in

Washington, D.C. was Miss Mabel Boardman. An active and energetic promoter, Miss Boardman had

been the moving force behind the Red Cross enterprise, although its endowment came from wealthy and

prominent persons including J. P. Morgan, Mrs. E. H. Harriman, Cleveland H. Dodge, and Mrs. Russell

Sage. The 1910 fund-raising campaign for $2 million, for example, was successful only because it was

supported by these wealthy residents of New York City. In fact, most of the money came from New York

City. J.P. Morgan himself contributed $100,000 and seven other contributors in New York City amassed

$300,000. Only one person outside New York City contributed over $10,000 and that was William J.

Boardman, Miss Boardman's father. Henry P. Davison was chairman of the 1910 New York Fund Raising

Committee and later became chairman of the War Council of the American Red Cross. In other

words, in World War I the Red Cross depended heavily on Wall Street, and specifically on the Morgan

firm.

The Red Cross was unable to cope with the demands of World War I and in effect was taken over by

these New York bankers. According to John Foster Dulles, these businessmen "viewed the American Red

Cross as a virtual arm of government, they envisaged making an incalculable contribution to the winning

of the war."1 In so doing they made a mockery of the Red Cross motto: "Neutrality and Humanity."

In exchange for raising funds, Wall Street asked for the Red Cross War Council; and on the

recommendation of Cleveland H. Dodge,(L) one of Woodrow Wilson's financial backers, Henry P. Davison(R),

a partner in J.P. Morgan Company, became chairman. The list of administrators of the Red Cross then

began to take on the appearance of the New York Directory of Directors: John D. Ryan, president of

Anaconda Copper Company (see frontispiece); George W. Hill, president of the American Tobacco

Company; Grayson M.P. Murphy, vice president of the Guaranty Trust Company; and Ivy Lee, public

relations expert for the Rockefeller's. Harry Hopkins, later to achieve fame under President Roosevelt,

became assistant to the general manager of the Red Cross in Washington, D.C.

The question of a Red Cross Mission to Russia came before the third meeting of this reconstructed War

Council, which was held in the Red Cross Building, Washington, D.C., on Friday, May 29, 1917, at 11:00

A.M. Chairman Davison was deputed to explore the idea with Alexander Legge of the International Harvester Company. Subsequently International Harvester, which had considerable interests in Russia,

provided $200,000 to assist financing the Russian mission. At a later meeting it was made known that

William Boyce Thompson, director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, had "offered to pay the

entire expense of the commission"; this offer was accepted in a telegram: "Your desire to pay expenses of

commission to Russia is very much appreciated and from our point of view very important."2

The members of the mission received no pay. All expenses were paid by William Boyce Thompson and

the $200,000 from International Harvester was apparently used in Russia for political subsidies. We know

from the files of the U.S. embassy in Petrograd that the U.S. Red Cross gave 4,000 rubles to Prince Lvoff,

president of the Council of Ministers, for "relief of revolutionists" and 10,000 rubles in two payments to

Kerensky for "relief of political refugees."

AMERICAN RED CROSS

MISSION TO RUSSIA, 1917

In August 1917 the American Red Cross Mission to Russia had only a nominal relationship with the

American Red Cross, and must truly have been the most unusual Red Cross Mission in history. All

expenses, including those of the uniforms — the members were all colonels, majors, captains, or

lieutenants — were paid out of the pocket of William Boyce Thompson. One contemporary observer

dubbed the all-officer group an "Haytian Army":

The American Red Cross delegation, about forty Colonels, Majors, Captains and

Lieutenants, arrived yesterday. It is headed by Colonel (Doctor) Billings of Chicago, and

includes Colonel William B. Thompson and many doctors and civilians, all with military

titles; we dubbed the outfit the "Haytian Army" because there were no privates. They

have come to fill no clearly defined mission, as far as I can find out, in fact Gov. Francis

told me some time ago that he had urged they not be allowed to come, as there were

already too many missions from the various allies in Russia. Apparently, this

Commission imagined there was urgent call for doctors and nurses in Russia; as a matter

of fact there is at present a surplus of medical talent and nurses, native and foreign in the

country and many haft-empty hospitals in the large cities.3

The mission actually comprised only twenty-four (not forty), having military rank from lieutenant colonel

down to lieutenant, and was supplemented by three orderlies, two motion-picture photographers, and two

interpreters, without rank. Only five (out of twenty-four) were doctors; in addition, there were two

medical researchers. The mission arrived by train in Petrograd via Siberia in August 1917. The five

doctors and orderlies stayed one month, returning to the United States on September 11. Dr. Frank

Billings, nominal head of the mission and professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, was

reported to be disgusted with the overtly political activities of the majority of the mission. The other

medical men were William S. Thayer, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University; D. J.

McCarthy, Fellow of Phipps Institute for Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, at Philadelphia; Henry C.

Sherman, professor of food chemistry at Columbia University; C. E. A. Winslow, professor of

bacteriology and hygiene at Yale Medical School; Wilbur E. Post, professor of medicine at Rush Medical

College; Dr. Malcolm Grow, of the Medical Officers Reserve Corps of the U.S. Army; and Orrin

Wightman, professor of clinical medicine, New York Polyclinic Hospital. George C. Whipple was listed

as professor of sanitary engineering at Harvard University but in fact was partner of the New York firm of

Hazen, Whipple & Fuller, engineering consultants. This is significant because Malcolm Pirnie — of whom

more later — was listed as an assistant sanitary engineer and employed as an engineer by Hazen, Whipple

& Fuller.

.jpg/220px-William_B._Thompson_(ca_1912).jpg)

William B. Thompson

The majority of the mission, as seen from the table, was made up of lawyers, financiers, and their

assistants, from the New York financial district. The mission was financed by William B. Thompson,described in the official Red Cross circular as "Commissioner and Business Manager; Director United

States Federal Bank of New York." Thompson brought along Cornelius Kelleher, described as an attache

to the mission but actually secretary to Thompson and with the same address — 14 Wall Street, New York

City. Publicity for the mission was handled by Henry S. Brown, of the same address. Thomas Day

Thacher was an attorney with Simpson, Thacher & Bartlett, a firm founded by his father, Thomas

Thacher, in 1884 and prominently involved in railroad reorganization and mergers. Thomas as junior first

worked for the family firm, became assistant U.S. attorney under Henry L. Stimson, and returned to the

family firm in 1909. The young Thacher was a close friend of Felix Frankfurter and later became assistant

to Raymond Robins, also on the Red Cross Mission. In 1925 he was appointed district judge under

President Coolidge, became solicitor general under Herbert Hoover, and was a director of the William

Boyce Thompson Institute.

THE 1917 AMERICAN RED

CROSS MISSION TO RUSSIA

Members from Wall Street

financial community and their

affiliations.

Andrews (Liggett & Myers

Tobacco)

Barr (Chase National Bank)

Brown (c/o William B.

Thompson)

Cochran (McCann Co.)

Kelleher (c/o William B.

Thompson)

Nicholson (Swirl & Co.)

Pirnie (Hazen, Whipple & Fuller)

Redfield (Stetson, Jennings &

Russell)

Robins (mining promoter)

Swift (Swift & Co.)

Thacher (Simpson, Thacher &

Bartlett)

Thompson (Federal Reserve Bank

of N.Y.)

Wardwell (Stetson, Jennings &

Russell)

Whipple (Hazen, Whipple &

Fuller)

Corse (National City Bank)

Magnuson (recommended by

confidential agent of Colonel

Thompson)

Medical

doctors

Billings (doctor)

Grow (doctor)

McCarthy (medical research;

doctor)

Post (doctor)

Sherman (food chemistry)

Thayer (doctor)

Wightman (medicine)

Winslow (hygiene)

Orderlies,

interpreters,

etc.

Brooks (orderly)

Clark (orderly)

Rocchia (orderly)

Travis (movies)

Wyckoff (movies)

Hardy (justice)

Horn (transportation)

Alan Wardwell, also a deputy commissioner and secretary to the chairman, was a lawyer with the law

firm of Stetson, Jennings & Russell of 15 Broad Street, New York City, and H. B. Redfield was law

secretary to Wardwell. Major Wardwell was the son of William Thomas Wardwell, long-time treasurer of

Standard Oil of New Jersey and Standard Oil of New York. The elder Wardwell was one of the signers of

the famous Standard Oil trust agreement, a member of the committee to organize Red Cross activities in

the Spanish American War, and a director of the Greenwich Savings Bank. His son Alan was a director

not only of Greenwich Savings, but also of Bank of New York and Trust Co. and the Georgian

Manganese Company (along with W. Averell Harriman, a director of Guaranty Trust). In 1917 Alan

Wardwell was affiliated with Stetson, Jennings 8c Russell and later joined Davis, Polk, Wardwell,

Gardner & Read (Frank L. Polk was acting secretary of state during the Bolshevik Revolution period).

The Senate Overman Committee noted that Wardwell was favorable to the Soviet regime although Poole,

the State Department official on the spot, noted that "Major Wardwell has of all Americans the widest

personal knowledge of the terror" (316-23-1449). In the 1920's Wardwell became active with the Russian/American

Chamber of Commerce in promoting Soviet trade objectives.

The treasurer of the mission was James W. Andrews, auditor of Liggett & Myers Tobacco Company of

St. Louis. Robert I. Barr, another member, was listed as a deputy commissioner; he was a vice president

of Chase Securities Company (120 Broadway) and of the Chase National Bank. Listed as being in charge

of advertising was William Cochran of 61 Broadway, New York City. Raymond Robins, a mining

promoter, was included as a deputy commissioner and described as "a social economist." Finally, the

mission included two members of Swift & Company of Union Stockyards, Chicago. The Swifts have

been previously mentioned as being connected with German espionage in the United States during World

War I. Harold H. Swift, deputy commissioner, was assistant to the vice president of Swift & Company;

William G. Nicholson was also with Swift & Company, Union Stockyards.

Two persons were unofficially added to the mission after it arrived in Petrograd: Frederick M. Corse,

representative of the National City Bank in Petrograd; and Herbert A. Magnuson, who was "very highly

recommended by John W. Finch, the confidential agent in China of Colonel William B. Thompson."4

The Pirnie papers, deposited at the Hoover Institution, contain primary material on the mission. Malcolm

Pirnie was an engineer employed by the firm of Hazen, Whipple & Fuller, consulting engineers, of 42

Street, New York City. Pirnie was a member of the mission, listed on a manifest as an assistant sanitary

engineer. George C. Whipple, a partner in the firm, was also included in the group. The Pirnie papers

include an original telegram from William B. Thompson, inviting assistant sanitary engineer Pirnie to

meet with him and Henry P. Davison, chairman of the Red Cross War Council and partner in the J.P.

Morgan firm, before leaving for Russia. The telegram reads as follows:

WESTERN UNION TELEGRAM New York, June 21, 1917

To Malcolm Pirnie

I should very much like to have you dine with me at the Metropolitan Club, Sixteenth

Street and Fifth Avenue New York City at eight o'clock tomorrow Friday evening to

meet Mr. H. P. Davison.

W. B. Thompson, 14 Wall Street

The files do not elucidate why Morgan partner Davison and Thompson, director of the Federal Reserve

Bank — two of the most prominent financial men in New York — wished to have dinner with an assistant

sanitary engineer about to leave for Russia. Neither do the files explain why Davison was subsequently

unable to meet Dr. Billings and the commission itself, nor why it was necessary to advise Pirnie of his

inability to do so. But we may surmise that the official cover of the mission — Red Cross activities — was

of significantly less interest than the Thompson-Pirnie activities, whatever they may have been. We do

know that Davison wrote to Dr. Billings on June 25, 1917:

Dear Doctor Billings:

It is a disappointment to me and to my associates on the War Council not have been able

to meet in a body the members of your Commission ....

A copy of this letter was also mailed to assistant sanitary engineer Pirnie with a personal letter from

Morgan banker Henry P. Davison, which read:

My dear Mr. Pirnie:

You will, I am sure, entirely understand the reason for the letter to Dr. Billings, copy of

which is enclosed, and accept it in the spirit in which it is sent ....

The purpose of Davison's letter to Dr. Billings was to apologize to the commission and Billings for being

unable to meet with them. We may then be justified in supposing that some deeper arrangements were

made by Davison and Pirnie concerning the activities of the mission in Russia and that these

arrangements were known to Thompson. The probable nature of these activities will be described later.5

The American Red Cross Mission (or perhaps we should call it the Wall Street Mission to Russia) also

employed three Russian-English interpreters: Captain Ilovaisky, a Russian Bolshevik; Boris Reinstein, a

Russian-American, later secretary to Lenin, and the head of Karl Radek's Bureau of International

Revolutionary Propaganda, which also employed John Reed and Albert Rhys Williams; and Alexander

Gumberg (alias Berg, real name Michael Gruzenberg), who was a brother of Zorin, a Bolshevik minister.

Gumberg was also the chief Bolshevik agent in Scandinavia. He later became a confidential assistant to

Floyd Odlum of Atlas Corporation in the United States as well as an adviser to Reeve Schley, a vice

president of the Chase Bank.

It should be asked in passing: How useful were the translations supplied by these interpreters? On

September 13, 1918, H. A. Doolittle, American vice consul at Stockholm, reported to the secretary of

state on a conversation with Captain Ilovaisky (who was a "close personal friend" of Colonel Robins of

the Red Cross Mission) concerning a meeting of the Murman Soviet and the Allies. The question of

inviting the Allies to land at Murman was under discussion at the Soviet, with Major Thacher of the Red

Cross Mission acting for the Allies. Ilovaisky interpreted Thacher's views for the Soviet. "Ilovaisky spoke

at some length in Russian, supposedly translating for Thacher, but in reality for Trotsky .... "to the effect

that "the United States would never permit such a landing to occur and urging the speedy recognition of

the Soviets and their politics."6 Apparently Thacher suspected he was being mistranslated and expressed

his indignation. However, "Ilovaisky immediately telegraphed the substance to Bolshevik headquarters

and through their press bureau had it appear in all the papers as emanating from the remarks of Major

Thacher and as the general opinion of all truly accredited American representatives."7

Ilovaisky recounted to Maddin Summers, U.S. consul general in Moscow, several instances where he

(Ilovaisky) and Raymond Robins of the Red Cross Mission had manipulated the Bolshevik press,

especially "in regard to the recall of the Ambassador, Mr. Francis." He admitted that they had not been scrupulous, "but had acted according to their ideas of right, regardless of how they might have conflicted

with the politics of the accredited American representatives."8

This then was the American Red Cross Mission to Russia in 1917.

AMERICAN RED CROSS

MISSION TO ROMANIA

In 1917 the American Red Cross also sent a medical assistance mission to Romania, then fighting the

Central Powers as an ally of Russia. A comparison of the American Red Cross Mission to Russia with

that sent to Romania suggests that the Red Cross Mission based in Petrograd had very little official

connection with the Red Cross and even less connection with medical assistance. Whereas the Red Cross

Mission to Romania valiantly upheld the Red Cross twin principles of "humanity" and "neutrality," the

Red Cross Mission in Petrograd flagrantly abused both.

The American Red Cross Mission to Romania left the United States in July 1917 and located itself at

Jassy. The mission consisted of thirty persons under Chairman Henry W. Anderson, a lawyer from

Virginia. Of the thirty, sixteen were either doctors or surgeons. By comparison, out of twenty-nine

individuals with the Red Cross Mission to Russia, only three were doctors, although another four

members were from universities and specialized in medically related fields. At the most, seven could be

classified as doctors with the mission to Russia compared with sixteen with the mission to Romania.

There was about the same number of orderlies and nurses with both missions. The significant

comparison, however, is that the Romanian mission had only two lawyers, one treasurer, and one

engineer. The Russian mission had fifteen lawyers and businessmen. None of the Romanian mission

lawyers or doctors came from anywhere near the New York area but all, except one (an "observer" from

the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C.), of the lawyers and businessmen with the Russian

mission came from that area. Which is to say that more than half the total of the Russian mission came

from the New York financial district. In other words, the relative composition of these missions confirms

that the mission to Romania had a legitimate purpose — to practice medicine — while the Russian mission

had a non-medical and strictly political objective. From its personnel, it could be classified as a

commercial or financial mission, but from its actions it was a subversive political action group.

PERSONNEL WITH THE

AMERICAN RED CROSS

MISSIONS TO RUSSIA

AND ROMANIA, 1917

AMERICAN RED CROSS

MISSION TO

Personnel Russia Romania

Medical (doctors and surgeons) 7 16

Orderlies, nurses 7 10

Lawyers and businessmen 15 4

TOTAL 29 30

SOURCES:

American Red Cross, Washington, D.C.

U.S. Department of State, Petrograd embassy, Red Cross file, 1917.

The Red Cross Mission to Romania remained at its post in Jassy for the remainder of 1917 and into 1918.

The medical staff of the American Red Cross Mission in Russia — the seven doctors — quit in disgust in

August 1917, protested the political activities of Colonel Thompson, and returned to the United States.

Consequently, in September 1917, when the Romanian mission appealed to Petrograd for American

doctors and nurses to help out in the near crisis conditions in Jassy, there were no American doctors or

nurses in Russia available to go to Romania.

Whereas the bulk of the mission in Russia occupied its time in internal political maneuvering, the mission

in Romania threw itself into relief work as soon as it arrived. On September 17, 1917, a confidential cable

from Henry W. Anderson, chairman of the Romania mission, to the American ambassador Francis in

Petrograd requested immediate and urgent help in the form of $5 million to meet an impending

catastrophe in Romania. Then followed a series of letters, cables, and communications from Anderson to

Francis appealing, unsuccessfully, for help.

On September 28, 1917, Vopicka, American minister in Romania, cabled Francis at length, for relay to

Washington, and repeated Anderson's analysis of the Romanian crisis and the danger of epidemics — and

worse — as winter closed in:

Considerable money and heroic measures required prevent far reaching disaster ....

Useless try handle situation without someone with authority and access to government . .

. With proper organization to look after transport receive and distribute supplies.

The hands of Vopicka and Anderson were tied as all Romanian supplies and financial transactions were

handled by the Red Cross Mission in Petrograd — and Thompson and his staff of fifteen Wall Street

lawyers and businessmen apparently had matters of greater concern that Romanian Red Cross affairs.

There is no indication in the Petrograd embassy files at the U.S. State Department that Thompson,

Robins, or Thacher concerned himself at any time in 1917 or 1918 with the urgent situation in Romania.

Communications from Romania went to Ambassador Francis or to one of his embassy staff, and

occasionally through the consulate in Moscow.

By October 1917 the Romanian situation reached the crisis point. Vopicka cabled Davison in New York

(via Petrograd) on October 5:

Most urgent problem here .... Disastrous effect feared .... Could you possibly arrange

special shipment .... Must rush or too late.

Then on November 5 Anderson cabled the Petrograd embassy saying that delays in sending help had

already "cost several thousand lives." On November 13 Anderson cabled Ambassador Francis concerning

Thompson's lack of interest in Romanian conditions:

Requested Thompson furnish details all shipments as received but have not obtained

same .... Also requested him keep me posted as to transport conditions but received very

little information.

Anderson then requested that Ambassador Francis intercede on his behalf in order to have funds for the

Romanian Red Cross handled in a separate account in London, directly under Anderson and removed

from the control of Thompson's mission.

THOMPSON IN KERENSKY'S RUSSIA

What then was the Red Cross Mission doing? Thompson certainly acquired a reputation for opulent living

in Petrograd, but apparently he undertook only two major projects in Kerensky's Russia: support for an

American propaganda program and support for the Russian Liberty Loan. Soon after arriving in Russia

Thompson met with Madame Breshko-Breshkovskaya and David Soskice, Kerensky's secretary, and

agreed to contribute $2 million to a committee of popular education so that it could "have its own press

and... engage a staff of lecturers, with cinematograph illustrations" (861.00/ 1032); this was for the

propaganda purpose of urging Russia to continue in the war against Germany. According to Soskice, "a

packet of 50,000 rubles" was given to Breshko-Breshkovskaya with the statement, "This is for you to

expend according to your best judgment." A further 2,100,000 rubles was deposited into a current bank

account. A letter from J.P. Morgan to the State Department (861.51/190) confirms that Morgan cabled

425,000 rubles to Thompson at his request for the Russian Liberty Loan; J.P. also conveyed the interest

of the Morgan firm regarding "the wisdom of making an individual subscription through Mr. Thompson"

to the Russian Liberty Loan. These sums were transmitted through the National City Bank branch in

Petrograd.

THOMPSON GIVES THE

BOLSHEVIKS $1 MILLION

Of greater historical significance, however, was the assistance given to the Bolsheviks first by Thompson,

then, after December 4, 1917, by Raymond Robins.

Thompson's contribution to the Bolshevik cause was recorded in the contemporary American press. The

Washington Post of February 2, 1918, carried the following paragraphs:

GIVES BOLSHEVIKS A MILLION

W. B. Thompson, Red Cross Donor, Believes Party Misrepresented. New York, Feb. 2

(1918). William B. Thompson, who was in Petrograd from July until November last, has

made a personal contribution of $1,000,000 to the Bolsheviki for the purpose of

spreading their doctrine in Germany and Austria.

Mr. Thompson had an opportunity to study Russian conditions as head of the American

Red Cross Mission, expenses of which also were largely defrayed by his personal

contributions. He believes that the Bolshevik's constitute the greatest power against Pro Germanism

in Russia and that their propaganda has been undermining the militarist

regimes of the General Empires.

Mr. Thompson deprecates American criticism of the Bolsheviki. He believes they have

been misrepresented and has made the financial contribution to the cause in the belief

that it will be money well spent for the future of Russia as well as for the Allied cause.

Hermann Hagedorn's biography The Magnate: William Boyce Thompson and His Time (1869-1930)

reproduces a photograph of a cablegram from J.P. Morgan in New York to W. B. Thompson, "Care American Red Cross, Hotel Europe, Petrograd." The cable is date-stamped, showing it was received at

Petrograd "8-Dek 1917" (8 December 1917), and reads:

New York Y757/5 24W5 Nil — Your cable second received. We have paid National City

Bank one million dollars as instructed — Morgan.

The National City Bank branch in Petrograd had been exempted from the Bolshevik nationalization

decree — the only foreign or domestic Russian bank to have been so exempted. Hagedorn says that this

million dollars paid into Thompson's NCB account was used for "political purposes."

SOCIALIST MINING PROMOTER

RAYMOND ROBINS 9

William B. Thompson left Russia in early December 1917 to return home. He traveled via London,

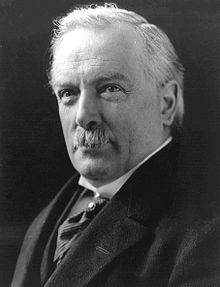

where, in company with Thomas Lamont of the J.P. Morgan firm, he visited Prime Minister Lloyd

George, an episode we pick up in the next chapter. His deputy, Raymond Robins, was left in charge of the

Red Cross Mission to Russia. The general impression that Colonel Robins presented in the subsequent

months was not overlooked by the press. In the words of the Russian newspaper Russkoe Slovo, Robins

"on the one hand represents American labor and on the other hand American capital, which is

endeavoring through the Soviets to gain their Russian markets."10

Raymond Robins started life as the manager of a Florida phosphate company commissary. From this base

he developed a kaolin deposit, then prospected Texas and the Indian territories in the late nineteenth

century. Moving north to Alaska, Robins made a fortune in the Klondike gold rush. Then, for no

observable reason, he switched to socialism and the reform movement. By 1912 he was an active member

of Roosevelt's Progressive Party. He joined the 1917 American Red Cross Mission to Russia as a "social

economist."

There is considerable evidence, including Robins' own statements, that his reformist social-good appeals

were little more than covers for the acquisition of further power and wealth, reminiscent of Frederick

Howe's suggestions in Confessions of a Monopolist. For example, in February 1918 Arthur Bullard was in

Petrograd with the U.S. Committee on Public Information and engaged in writing a long memorandum

for Colonel Edward House. This memorandum was given to Robins by Bullard for comments and

criticism before transmission to House in Washington, D.C. Robins' very unsocialistic and imperialistic

comments were to the effect that the manuscript was "uncommonly discriminating, far-seeing and well

done," but that he had one or two reservations — in particular, that recognition of the Bolsheviks was long

overdue, that it should have been effected immediately, and that had the U.S. so recognized the

Bolsheviks, "I believe that we would now be in control of the surplus resources of Russia and have

control officers at all points on the frontier."11

This desire to gain "control of the surplus resources of Russia" was also obvious to Russians. Does this

sound like a social reformer in the American Red Cross or a Wall Street mining promoter engaged in the

practical exercise of imperialism?

In any event, Robins made no bones about his support for the Bolshevik's.12 Barely three weeks after the

Bolshevik phase of the Revolution started, Robins cabled Henry Davison at Red Cross headquarters:

"Please urge upon the President the necessity of our continued intercourse with the Bolshevik

Government." Interestingly, this cable was in reply to a cable instructing Robins that the "President

desires the withholding of direct communications by representatives of the United States with the

Bolshevik Government."13 Several State Department reports complained about the partisan nature of

Robins' activities. For example, on March 27, 1919, Harris, the American consul at Vladivostok,commented on a long conversation he had had with Robins and protested gross inaccuracies in the latter's

reporting. Harris wrote, "Robins stated to me that no German and Austrian prisoners of war had joined

the Bolshevik army up to May 1918. Robbins knew this statement was absolutely false." Harris then

proceeded to provide the details of evidence available to Robins.14

Harris concluded, "Robbins deliberately misstated facts concerning Russia at that time and he has been

doing it ever since."

On returning to the United States in 1918, Robins continued his efforts in behalf of the Bolsheviks. When

the files of the Soviet Bureau were seized by the Lusk Committee, it was found that Robins had had

"considerable correspondence" with Ludwig Martens and other members of the bureau. One of the more

interesting documents seized was a letter from Santeri Nuorteva (alias Alexander Nyberg), the first Soviet

representative in the U.S., to "Comrade Cahan," editor of the New York Daily Forward. The letter called

on the party faithful to prepare the way for Raymond Robins:

(To Daily) FORWARD July 6, 1918

Dear Comrade Cahan:

It is of the utmost importance that the Socialist press set up a clamor immediately that

Col. Raymond Robins, who has just returned from Russia at the head of the Red Cross

Mission, should be heard from in a public report to the American people. The armed

intervention danger has greatly increased. The reactionists are using the Czecho-Slovak

adventure to bring about invasion. Robins has all the facts about this and about the

situation in Russia generally. He takes our point of view.

I am enclosing copy of Call editorial which shows a general line of argument, also some

facts about Czecho-Slovaks.

Fraternally,

PS&AU Santeri Nuorteva

THE INTERNATIONAL RED

CROSS AND REVOLUTION

Unknown to its administrators, the Red Cross has been used from time to time as a vehicle or cover for

revolutionary activities. The use of Red Cross markings for unauthorized purposes is not uncommon.

When Czar Nicholas was moved from Petrograd to Tobolsk allegedly for his safety (although this

direction was towards danger rather than safety), the train carried Japanese Red Cross placards. The State

Department files contain examples of revolutionary activity under cover of Red Cross activities. For

example, a Russian Red Cross official (Chelgajnov) was arrested in Holland in 1919 for revolutionary

acts (316-21-107). During the Hungarian Bolshevik revolution in 1918, led by Bela Kun, Russian

members of the Red Cross (or revolutionaries operating as members of the Russian Red Cross) were found in Vienna and Budapest. In 1919 the U.S. ambassador in London cabled Washington startling

news; through the British government he had learned that "several Americans who had arrived in this

country in the uniform of the Red Cross and who stated that they were Bolsheviks . . . were proceeding

through France to Switzerland to spread Bolshevik propaganda." The ambassador noted that about 400

American Red Cross people had arrived in London in November and December 1918; of that number one

quarter returned to the United States and "the remainder insisted on proceeding to France." There was a

later report on January 15, 1918, to the effect that an editor of a labor newspaper in London had been

approached on three different occasions by three different American Red Cross officials who offered to

take commissions to Bolsheviks in Germany. The editor had suggested to the U.S. embassy that it watch

American Red Cross personnel. The U.S. State Department took these reports seriously and Polk cabled

for names, stating, "If true, I consider it of the greatest importance" (861.00/3602 and /3627).

To summarize: the picture we form of the 1917 American Red Cross Mission to Russia is remote from

one of neutral humanitarianism. The mission was in fact a mission of Wall Street financiers to influence

and pave the way for control, through either Kerensky or the Bolshevik revolutionaries, of the Russian

market and resources. No other explanation will explain the actions of the mission. However, neither

Thompson nor Robins was a Bolshevik. Nor was either even a consistent socialist. The writer is inclined

to the interpretation that the socialist appeals of each man were covers for more prosaic objectives. Each

man was intent upon the commercial; that is, each sought to use the political process in Russia for

personal financial ends. Whether the Russian people wanted the Bolsheviks was of no concern. Whether

the Bolshevik regime would act against the United States — as it consistently did later — was of no

concern. The single overwhelming objective was to gain political and economic influence with the new

regime, whatever its ideology. If William Boyce Thompson had acted alone, then his directorship of the

Federal Reserve Bank would be inconsequential. However, the fact that his mission was dominated by

representatives of Wall Street institutions raises a serious question — in effect, whether the mission was a

planned, premeditated operation by a Wall Street syndicate. This the reader will have to judge for

himself, as the rest of the story unfolds.

Chapter VI

CONSOLIDATION AND EXPORT

OF THE REVOLUTION

Marx's great book Das Kapital is at once a monument of reasoning and a

storehouse of facts.

Lord Milner, member of the

British War Cabinet, 1917,

and director of the

London Joint Stock Bank

William Boyce Thompson is an unknown name in twentieth-century history, yet Thompson

played a crucial role in the Bolshevik Revolution.1 Indeed, if Thompson had not been in Russia

in 1917, subsequent history might have followed a quite different course. Without the financial

and, more important, the diplomatic and propaganda assistance given to Trotsky and Lenin by

Thompson, Robins, and their New York associates, the Bolsheviks may well have withered

away and Russia evolved into a socialist but constitutional society.

Who was William Boyce Thompson? Thompson was a promoter of mining stocks, one of the

best in a high-risk business. Before World War I he handled stock-market operations for the

Guggenheim copper interests. When the Guggenheims needed quick capital for a stock-market

struggle with John D. Rockefeller, it was Thompson who promoted Yukon Consolidated

Goldfields before an unsuspecting public to raise a $3.5 million war chest. Thompson was

manager of the Kennecott syndicate, another Guggenheim operation, valued at $200 million. It

was Guggenheim Exploration, on the other hand, that took up Thompson's options on the rich

Nevada Consolidated Copper Company. About three quarters of the original Guggenheim

Exploration Company was controlled by the Guggenheim family, the Whitney family (who

owned Metropolitan magazine, which employed the Bolshevik John Reed), and John Ryan. In

1916 the Guggenheim interests reorganized into Guggenheim Brothers and brought in William

C. Potter, who was formerly with Guggenheim's American Smelting and Refining Company

but who was in 1916 first' vice president of Guaranty Trust.

Extraordinary skill in raising capital for risky mining promotions earned Thompson a personal

fortune and directorships in Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company, Nevada Consolidated

Copper Company, and Utah Copper Company — all major domestic copper producers. Copper

is, of course, a major material in the manufacture of munitions. Thompson was also director of

the Chicago Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, the Magma Arizona Railroad and the

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. And of particular interest for this book, Thompson was

"one of the heaviest stockholders in the Chase National Bank." It was Albert H. Wiggin,

president of the Chase Bank, who pushed Thompson for a post in the Federal Reserve System;

and in 1914 Thompson became the first full-term director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New

York — the most important bank in the Federal Reserve System.

By 1917, then, William Boyce Thompson was a financial operator of substantial means,

demonstrated ability, with a flair for promotion and implementation of capitalist projects, and with ready access to the centers of political and financial power. This was the same man who

first supported Aleksandr Kerensky, and who then became an ardent supporter of the

Bolsheviks, bequeathing a surviving symbol of this support — a laudatory pamphlet in Russian,

"Pravda o Rossii i Bol'shevikakh."2

Raymond Robins

Before leaving Russia in early December 1917 Thompson handed over the American Red

Cross Mission to his deputy Raymond Robins. Robins then organized Russian revolutionaries

to implement the Thompson plan for spreading Bolshevik propaganda in Europe (see Appendix

3). A French government document confirms this: "It appeared that Colonel Robins . . . was

able to send a subversive mission of Russian Bolsheviks to Germany to start a revolution

there."3 This mission led to the abortive German Spartacist revolt of 1918. The overall plan

also included schemes for dropping Bolshevik literature by airplane or for smuggling it across

German lines.

Thompson made preparations in late 1917 to leave Petrograd and sell the Bolshevik Revolution

to governments in Europe and to the U.S. With this in mind, Thompson cabled Thomas W.

Lamont, a partner in the Morgan firm who was then in Paris with Colonel E. M. House.

Lamont recorded the receipt of this cablegram in his biography:

Just as the House Mission was completing its discussions in Paris in December

1917, I received an arresting cable from my old school and business friend,

William Boyce Thompson, who was then in Petrograd in charge of the

American Red Cross Mission there.4

Lamont journeyed to London and met with Thompson, who had left Petrograd on December 5,

traveled via Bergen, Norway, and arrived in London on December 10. The most important

achievement of Thompson and Lamont in London was to convince the British War Cabinet —

then decidedly anti-Bolshevik — that the Bolshevik regime had come to stay, and that British

policy should cease to be anti-Bolshevik, should accept the new realities, and should support

Lenin and Trotsky. Thompson and Lamont left London on December 18 and arrived in New

York on December 25, 1917. They attempted the same process of conversion in the United

States.

A CONSULTATION WITH LLOYD GEORGE

The secret British War Cabinet papers are now available and record the argument used by

Thompson to sell the British government on a pro-Bolshevik policy. The prime minister of

Great Britain was David Lloyd George. Lloyd George's private and political machinations

rivaled those of a Tammany Hall politician — yet in his lifetime and for decades after,

biographers were unable, or unwilling, to come to grips with them. In 1970 Donald

McCormick's The Mask of Merlin lifted the veil of secrecy. McCormick shows that by 1917

David Lloyd George had bogged "too deeply in the mesh of international armaments intrigues

to be a free agent" and was beholden to Sir Basil Zaharoff, an international armaments dealer,

whose considerable fortune was made by selling arms to both sides in several wars.5 Zaharoff

wielded enormous behind-the-scenes power and, according to McCormick, was consulted on

war policies by the Allied leaders. On more than one occasion, reports McCormick, Woodrow

Wilson, Lloyd George, and Georges Clemenceau met in Zaharoff's Paris home. McCormick notes that "Allied statesmen and leaders were obliged to consult him before planning any great

attack." British intelligence, according to McCormick, "discovered documents which

incriminated servants of the Crown as secret agents of Sir Basil Zaharoff with the knowledge of

Lloyd George."6 In 1917 Zaharoff was linked to the Bolsheviks; he sought to divert munitions

away from anti-Bolsheviks and had already intervened in behalf of the Bolshevik regime in

both London and Paris.

Lord Milner

In late 1917, then — at the time Lamont and Thompson arrived in London — Prime Minister

Lloyd George was indebted to powerful international armaments interests that were allied to

the Bolsheviks and providing assistance to extend Bolshevik power in Russia. The British

prime minister who met with William Thompson in 1917 was not then a free agent; Lord

Milner was the power behind the scenes and, as the epigraph to this chapter suggests, favorably

inclined towards socialism and Karl Marx.

The "secret" War Cabinet papers give the "Prime Minister's account of a conversation with Mr.

Thompson, an American returned from Russia,"7 and the report made by the prime minister to

the War Cabinet after meeting with Thompson.8 The cabinet paper reads as follows:

The Prime Minister reported a conversation he had had with a Mr.

Thompson — an American traveler and a man of considerable means — who

had just returned from Russia, and who had given a somewhat different

impression of affairs in that country from what was generally believed. The

gist of his remarks was to the effect that the Revolution had come to stay; that

the Allies had not shown themselves sufficiently sympathetic with the

Revolution; and that MM. Trotsky and Lenin were not in German pay, the

latter being a fairly distinguished Professor. Mr. Thompson had added that he

considered the Allies should conduct in Russia an active propaganda, carried

out by some form of Allied Council composed o[ men especially selected [or

the purpose; further, that on the whole, he considered, having regard to the

character of the de facto Russian Government, the several Allied Governments

were not suitably represented in Petrograd. In Mr. Thompson's opinion, it was

necessary for the Allies to realize that the Russian army and people were out of

the war, and that the Allies would have to choose between Russia as the

friendly or a hostile neutral.

The question was discussed as to whether the Allies ought not to change their

policy in regard to the de facto Russian Government, the Bolsheviks being

stated by Mr. Thompson to be anti-German. In this connection Lord Robert

Cecil drew attention to the conditions of the armistice between the German

and Russian armies, which provided, inter alia, for trading between the two

countries, and for the establishment of a Purchasing Commission in Odessa,

the whole arrangement being obviously dictated by the Germans. Lord Robert

Cecil expressed the view that the Germans would endeavour to continue the

armistice until the Russian army had melted away.

Sir Edward Carson read a communication, signed by M. Trotsky, which had

been sent to him by a British subject, the manager of the Russian branch of the

Vauxhall Motor Company, who had just returned from Russia [Paper G.T. —3040]. This report indicated that M. Trotsky's policy was, ostensibly at any

rate, one of hostility to the organisation of civilized society rather than pro German.

On the other hand, it was suggested that an assumed attitude of this

kind was by no means inconsistent with Trotsky's being a German agent,

whose object was to ruin Russia in order that Germany might do what she

desired in that country.

After hearing Lloyd George's report and supporting arguments, the War Cabinet decided to go

along with Thompson and the Bolsheviks. Milner had a former British consul in Russia —

Bruce Lockhart — ready and waiting in the wings. Lockhart was briefed and sent to Russia with

instructions to work informally with the Soviets.

The thoroughness of Thompson's work in London and the pressure he was able to bring to bear

on the situation are suggested by subsequent reports coming into the hands of the War Cabinet,

from authentic sources. The reports provide a quite different view of Trotsky and the

Bolsheviks from that presented by Thompson, and yet they were ignored by the cabinet. In

April 1918 General Jan Smuts reported to the War Cabinet his talk with General Nieffel, the

head of the French Military Mission who had just returned from Russia:

Trotsky (sic) . . . was a consummate scoundrel who may not be pro-German,

but is thoroughly pro-Trotsky and pro-revolutionary and cannot in any way be

trusted. His influence is shown by the way he has come to dominate Lockhart,

Robins and the French representative. He [Nieffel] counsels great prudence in

dealing with Trotsky, who he admits is the only really able man in Russia.9

Several months later Thomas D. Thacher, Wall Street lawyer and another member of the

American Red Cross Mission to Russia, was in London. On April 13, 1918, Thacher wrote to

the American ambassador in London to the effect that he had received a request from H. P.

Davison, a Morgan partner, "to confer with Lord Northcliffe" concerning the situation in

Russia and then to go on to Paris "for other conferences." Lord Northcliffe was ill and Thacher

left with yet another Morgan partner, Dwight W. Morrow, a memorandum to be submitted to

Northcliffe on his return to London.10 This memorandum not only made explicit suggestions

about Russian policy that supported Thompson's position but even stated that "the fullest

assistance should be given to the Soviet government in its efforts to organize a volunteer

revolutionary army." The four main proposals in this Thacher report are:

First of all . . . the Allies should discourage Japanese intervention in Siberia.

In the second place, the fullest assistance should be given to the Soviet

Government in its efforts to organize a volunteer revolutionary army.

Thirdly, the Allied Governments should give their moral support to the

Russian people in their efforts to work out their own political systems free

from the domination of any foreign power ....

Fourthly, until the time when open conflict shall result between the German

Government and the Soviet Government of Russia there will be opportunity for peaceful commercial penetration by German agencies in Russia. So long as

there is no open break, it will probably be impossible to entirely prevent such

commerce. Steps should, therefore, be taken to impede, so far as possible, the

transport of grain and raw materials to Germany from Russia.11

THOMPSON'S INTENTIONS AND OBJECTIVES

Why would a prominent Wall Street financier, and director of the Federal Reserve Bank, want

to organize and assist Bolshevik revolutionaries? Why would not one but several Morgan

partners working in concert want to encourage the formation of a Soviet "volunteer

revolutionary army" — an army supposedly dedicated to the overthrow of Wall Street, including

Thompson, Thomas Lamont, Dwight Morrow, the Morgan firm, and all their associates?

Thompson at least was straightforward about his objectives in Russia: he wanted to keep

Russia at war with Germany (yet he argued before the British War Cabinet that Russia was out

of the war anyway) and to retain Russia as a market for postwar American enterprise. The

December 1917 Thompson memorandum to Lloyd George describes these aims.12 The

memorandum begins, "The Russian situation is lost and Russia lies entirely open to unopposed

German exploitation .... "and concludes, "I believe that intelligent and courageous work will

still prevent Germany from occupying the field to itself and thus exploiting Russia at the

expense of the Allies." Consequently, it was German commercial and industrial exploitation of

Russia that Thompson feared (this is also reflected in the Thacher memorandum) and that

brought Thompson and his New York friends into an alliance with the Bolsheviks. Moreover,

this interpretation is reflected in a quasi-jocular statement made by Raymond Robins,

Thompson's deputy, to Bruce Lockhart, the British agent:

You will hear it said that I am the representative of Wall Street; that I am the

servant of William B. Thompson to get Altai copper for him; that I have

already got 500,000 acres of the best timber land in Russia for myself; that I

have already copped off the Trans-Siberian Railway; that they have given me a

monopoly of the platinum of Russia; that this explains my working for the

soviet .... You will hear that talk. Now, I do not think it is true, Commissioner,

but let us assume it is true. Let us assume that I am here to capture Russia for

Wall Street and American business men. Let us assume that you are a British

wolf and I am an American wolf, and that when this war is over we are going

to eat each other up for the Russian market; let us do so in perfectly frank, man

fashion, but let us assume at the same time that we are fairly intelligent

wolves, and that we know that if we do not hunt together in this hour the

German wolf will eat us both up, and then let us go to work.13

With this in mind let us take a look at Thompson's personal motivations. Thompson was a

financier, a promoter, and, although without previous interest in Russia, had personally

financed the Red Cross Mission to Russia and used the mission as a vehicle for political

maneuvering. From the total picture we can deduce that Thompson's motives were primarily

financial and commercial. Specifically, Thompson was interested in the Russian market, and

how this market could be influenced, diverted; and captured for postwar exploitation by a Wall

Street syndicate, or syndicates. Certainly Thompson viewed Germany as an enemy, but less a political enemy than an economic or a commercial enemy. German industry and German

banking were the real enemy. To outwit Germany, Thompson was willing to place seed money

on any political power vehicle that would achieve his objective. In other words, Thompson was

an American imperialist fighting against German imperialism, and this struggle was shrewdly

recognized and exploited by Lenin and Trotsky.

The evidence supports this apolitical approach. In early August 1917, William Boyce

Thompson lunched at the U.S. Petrograd embassy with Kerensky, Terestchenko, and the

American ambassador Francis. Over lunch Thompson showed his Russian guests a cable he

had just sent to the New York office of J.P. Morgan requesting transfer of 425,000 rubles to

cover a personal subscription to the new Russian Liberty Loan. Thompson also asked Morgan

to "inform my friends I recommend these bonds as the best war investment I know. Will be

glad to look after their purchasing here without compensation"; he then offered personally to

take up twenty percent of a New York syndicate buying five million rubles of the Russian loan.

Not unexpectedly, Kerensky and Terestchenko indicated "great gratification" at support from

Wall Street. And Ambassador Francis by cable promptly informed the State Department that

the Red Cross commission was "working harmoniously with me," and that it would have an

"excellent effect."14 Other writers have recounted how Thompson attempted to convince the

Russian peasants to support Kerensky by investing $1 million of his own money and U.S.

government funds on the same order of magnitude in propaganda activities. Subsequently, the

Committee on Civic Education in Free Russia, headed by the revolutionary "Grandmother"

Breshkovskaya, with David Soskice (Kerensky's private secretary) as executive, established

newspapers, news bureaus, printing plants, and speakers bureaus to promote the appeal —

"Fight the kaiser and save the revolution." It is noteworthy that the Thompson-funded

Kerensky campaign had the same appeal — "Keep Russia in the war" — as had his financial

support of the Bolsheviks. The common link between Thompson's support of Kerensky and his

support of Trotsky and Lenin was — "continue the war against Germany" and keep Germany

out of Russia.

In brief, behind and below the military, diplomatic, and political aspects of World War I, there

was another battle raging, namely, a maneuvering for postwar world economic power by

international operators with significant muscle and influence. Thompson was not a Bolshevik;

he was not even pro-Bolshevik. Neither was he pro-Kerensky. Nor was he even pro-American.

The overriding motivation was the capturing of the postwar Russian market. This was a

commercial, not an ideological, objective. Ideology could sway revolutionary operators like

Kerensky, Trotsky, Lenin et al., but not financiers.

The Lloyd George memorandum demonstrates Thompson's partiality for neither Kerensky nor

the Bolsheviks: "After the overthrow of the last Kerensky government we materially aided the

dissemination of the Bolshevik literature, distributing it through agents and by aeroplanes to the

Germany army."15 This was written in mid-December 1917, only five weeks after the start of

the Bolshevik Revolution, and less than four months after Thompson expressed his support of

Kerensky over lunch in the American embassy.

THOMPSON RETURNS

TO THE UNITED STATES

Thompson then returned and toured the United States with a public plea for recognition of the Soviets. In a speech to the Rocky Mountain Club of New York in January 1918, Thompson

called for assistance for the emerging Bolshevik government and, appealing to an audience

composed largely of Westerners, evoked the spirit of the American pioneers:

These men would not have hesitated very long about extending recognition

and giving the fullest help and sympathy to the workingman's government of

Russia, because in 1819 and the years following we had out there Bolshevik governments . . . and mighty good governments too....16

It strains the imagination to compare the pioneer experience of our Western frontier to the

ruthless extermination of political opposition then under way in Russia. To Thompson,

promoting this was no doubt looked upon as akin to his promotion of mining stocks in days

gone by. As for those in Thompson's audience, we know not what they thought; however, no

one raised a challenge. The speaker was a respected director of the Federal Reserve Bank of

New York, a self-made millionaire (and that counts for much). And after all, had he not just

returned from Russia? But all was not rosy. Thompson's biographer Hermann Hagedorn has

written that Wall Street was "stunned" that his friends were "shocked" and "said he had lost his

head, had turned Bolshevist himself."17

While Wall Street wondered whether he had indeed "turned Bolshevik," Thompson found

sympathy among fellow directors on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Co director W. L. Saunders, chairman of Ingersoll-Rand Corporation and a director of the F.R.B,

wrote President Wilson on October 17, 1918, stating that he was "in sympathy with the Soviet

form of Government"; at the same time he disclaimed any ulterior motive such as "preparing

now to get the trade of the world after the war.18

Most interesting of Thompson's fellow directors was George Foster Peabody, deputy chairman

of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and a close friend of socialist Henry George.

Peabody had made a fortune in railroad manipulation, as Thompson had made his fortune in the

manipulation of copper stocks. Peabody then became active in behalf of government ownership

of railroads, and openly adopted socialization.19 How did Peabody reconcile his private enterprise

success with promotion of government ownership? According to his biographer

Louis Ware, "His reasoning told him that it was important for this form of transport to be

operated as a public service rather than for the advantage of private interests." This high sounding

do-good reasoning hardly rings true. It would be more accurate to argue that given

the dominant political influence of Peabody and his fellow financiers in Washington, they

could by government control of railroads more easily avoid the rigors of competition. Through

political influence they could manipulate the police power of the state to achieve what they had

been unable, or what was too costly, to achieve under private enterprise. In other words, the

police power of the state was a means of maintaining a private monopoly. This was exactly as

Frederick C. Howe had proposed.20 The idea of a centrally planned socialist Russia must have

appealed to Peabody. Think of it — one gigantic state monopoly! And Thompson, his friend and

fellow director, had the inside track with the boys running the operation!21

THE UNOFFICIAL AMBASSADORS:

ROBINS, LOCKHART, AND SADOUL

The Bolsheviks for their part correctly assessed a lack of sympathy among the Petrograd

representatives of the three major Western powers: the United States, Britain and France. The

United States was represented by Ambassador Francis, undisguisedly out of sympathy with the

revolution. Great Britain was represented by Sir James Buchanan, who had strong ties to the czarist monarchy and was suspected of having helped along the Kerensky phase of the

revolution. France was represented by Ambassador Paleologue, overtly anti-Bolshevik. In early

1918 three additional personages made their appearance; they became de facto representatives

of these Western countries and edged out the officially recognized representatives.

Raymond Robins took over the Red Cross Mission from W. B. Thompson in early December

1917 but concerned himself more with economic and political matters than obtaining relief and

assistance for poverty-stricken Russia. On December 26, 1917, Robins cabled Morgan partner

Henry Davison, temporarily the director general of the American Red Cross: "Please urge upon

the President the necessity of our continued intercourse with the Bolshevik Government."22 On

January 23, 1918, Robins cabled Thompson, then in New York:

Soviet Government stronger today than ever before. Its authority and power

greatly consolidated by dissolution of Constituent Assembly .... Cannot urge

too strongly importance of prompt recognition of Bolshevik authority ....

Sisson approves this text and requests you to show this cable to Creel. Thacher

and Wardwell concur.23

Later in 1918, on his return to the United States, Robins submitted a report to Secretary of State

Robert Lansing containing this opening paragraph: "American economic cooperation with

Russia; Russia will welcome American assistance in economic reconstruction."24

Robins' persistent efforts in behalf of the Bolshevik cause gave him a certain prestige in the

Bolshevik camp, and perhaps even some political influence. The U.S. embassy in London

claimed in November 1918 that "Salkind owes his appointment, as Bolshevik Ambassador to

Switzerland, to an American . . . no other than Mr. Raymond Robins."25 About this time

reports began filtering into Washington that Robins was himself a Bolshevik; for example, the

following from Copenhagen, dated December 3, 1918:

Confidential. According to a statement made by Radek to George de

Patpourrie, late Austria Hungarian Consul General at Moscow, Colonel

Robbins [sic], formerly thief of the American Red Cross Mission to Russia, is

at present in Moscow negotiating with the Soviet Government and arts as the

intermediary between the Bolsheviks and their friends in the United States.

The impression seems to be in some quarters that Colonel Robbins is himself a

Bolshevik while others maintain that he is not but that his activities in Russia

have been contrary to the interest of Associated Governments.26

Materials in the files of the Soviet Bureau in New York, and seized by the Lusk Committee in

1919, confirm that both Robins and his wife were closely associated with Bolshevik activities

in the United States and with the formation of the Soviet Bureau in New York.27

The British government established unofficial relations with the Bolshevik regime by sending to Russia a young Russian-speaking agent, Bruce Lockhart. Lockhart was, in effect, Robins'

opposite number; but unlike Robins, Lockhart had direct channels to his Foreign Office.

Lockhart was not selected by the foreign secretary or the Foreign Office; both were dismayed

at the appointment. According to Richard Ullman, Lockhart was "selected for his mission by

Milner and Lloyd George themselves .." Maxim Litvinov, acting as unofficial Soviet

representative in Great Britain, wrote for Lockhart a letter of introduction to Trotsky; in it he

called the British agent "a thoroughly honest man who understands our position and

sympathizes with us."28

We have already noted the pressures on Lloyd George to take a pro-Bolshevik position,

especially those from William B. Thompson, and those indirectly from Sir Basil Zaharoff and

Lord Milner. Milner was, as the epigraph to this chapter suggests, exceedingly prosocialist.

Edward Crankshaw has succinctly outlined Milner's duality.

Some of the passages [in Milner] on industry and society . . . are passages

which any Socialist would be proud to have written. But they were not written

by a Socialist. They were written by "the man who made the Boer War." Some

of the passages on Imperialism and the white man's burden might have been

written by a Tory diehard. They were written by the student of Karl Marx.29

According to Lockhart, the socialist bank director Milner was a man who inspired in him "the

greatest affection and hero-worship."30 Lockhart recounts how Milner personally sponsored his

Russian appointment, pushed it to cabinet level, and after his appointment talked "almost daily"

with Lockhart. While opening the way for recognition of the Bolsheviks, Milner also promoted

financial support for their opponents in South Russia and elsewhere, as did Morgan in New

York. This dual policy is consistent with the thesis that the modus operandi of the politicized

internationalists — such as Milner and Thompson — was to place state money on any

revolutionary or counterrevolutionary horse that looked a possible winner. The

internationalists, of course, claimed any subsequent benefits. The clue is perhaps in Bruce

Lockhart's observation that Milner was a man who "believed in the highly organized state."31

The French government appointed an even more openly Bolshevik sympathizer, Jacques

Sadoul, an old friend of Trotsky.32

In sum, the Allied governments neutralized their own diplomatic representatives in Petrograd

and replaced them with unofficial agents more or less sympathetic to the Bolshevist's.

The reports of these unofficial ambassadors were in direct contrast to pleas for help addressed

to the West from inside Russia.

Maxim Gorky protested the betrayal of revolutionary ideals by

the Lenin-Trotsky group, which had imposed the iron grip of a police state in Russia:

We Russians make up a people that has never yet worked in freedom, that has

never yet had a chance to develop all its powers and its talents. And when I

think that the revolution gives us the possibility of free work, of a many-sided

joy in creating, my heart is tilled with great hope and joy, even in these cursed

days that are besmirched with blood and alcohol.

There is where begins the line of my decided and irreconcilable separation

[tom the insane actions of the People's Commissaries. I consider Maximalism

in ideas very useful for the boundless Russian soul; its task is to develop in

this soul great and bold needs, to call forth the so necessary fighting spirit and

activity, to promote initiative in this indolent soul and to give it shape and life

in general.

But the practical Maximalism of the Anarcho-Communists and visionaries

from the Smolny is ruinous for Russia and, above all, for the Russian working

class. The People's Commissaries handle Russia like material for an

experiment. The Russian people is for them what the Horse is for learned

bacteriologists who inoculate the horse with typhus so that the anti-typhus

lymph may develop in its blood. Now the Commissaries are trying such a

predestined-to-failure experiment upon the Russian people without thinking

that the tormented, half-starved horse may die.

The reformers from the Smolny do not worry about Russia. They are cold bloodily sacrificing Russia in the name of their dream of the worldwide and

European revolution. And just as long as I can, I shall impress this upon the

Russian proletarian: "Thou art being led to destruction} Thou art being used as

material for an inhuman experiment!"33

Also in contrast to the reports of the sympathetic unofficial ambassadors were the reports from

the old-line diplomatic representatives. Typical of many messages flowing into Washington in

early 1918 — particularly after Woodrow Wilson's expression of support for the Bolshevik

governments — was the following cable from the U.S. legation in Bern, Switzerland:

For Polk. President's message to Consul Moscow not understood here and

people are asking why the President expresses support of Bolsheviki, in view

of raping, murder and anarchy of these bands.34

Continued support by the Wilson administration for the Bolsheviks led to the resignation of De

Witt C. Poole, the capable American charge d'affaires in Archangel (Russia):

It is my duty to explain frankly to the department the perplexity into which I

have been thrown by the statement of Russian policy adopted by the Peace

Conference, January 22, on the motion of the President. The announcement

very happily recognizes the revolution and confirms again that entire absence

of sympathy for any form of counter revolution which has always been a key

note of American policy in Russia, but it contains not one [word] of

condemnation for the other enemy of the revolution — the Bolshevik

Government.35

Thus even in the early days of 1918 the betrayal of the libertarian revolution had been noted by

such acute observers as Maxim Gorky and De Witt C. Poole. Poole's resignation shook the

State Department, which requested the "utmost reticence regarding your desire to resign" and

stated that "it will be necessary to replace you in a natural and normal manner in order to prevent grave and perhaps disastrous effect upon the morale of American troops in the

Archangel district which might lead to loss of American lives."36

So not only did Allied governments neutralize their own government representatives but the

U.S. ignored pleas from within and without Russia to cease support of the Bolsheviks.

Influential support of the Soviets came heavily from the New York financial area (little

effective support emanated from domestic U.S. revolutionaries). In particular, it came from

American International Corporation, a Morgan-controlled firm.

EXPORTING THE REVOLUTION:

JACOB H. RUBIN

We are now in a position to compare two cases — not by any means the only such cases — in

which American citizens Jacob Rubin and Robert Minor assisted in exporting the revolution to

Europe and other parts of Russia.

Jacob H. Rubin was a banker who, in his own words, "helped to form the Soviet Government

of Odessa."37 Rubin was president, treasurer, and secretary of Rubin Brothers of 19 West 34

Street, New York City. In 1917 he was associated with the Union Bank of Milwaukee and the

Provident Loan Society of New York. The trustees of the Provident Loan Society included

persons mentioned elsewhere as having connection with the Bolshevik Revolution: P. A.

Rockefeller, Mortimer L. Schiff, and James Speyer.

By some process — only vaguely recounted in his book I Live to Tell 38 — Rubin was in Odessa

in February 1920 and became the subject of a message from Admiral McCully to the State

Department (dated February 13, 1920, 861.00/6349). The message was to the effect that Jacob

H. Rubin of Union Bank, Milwaukee, was in Odessa and desired to remain with the

Bolshevists — "Rubin does not wish to leave, has offered his services to Bolsheviks and

apparently sympathizes with them." Rubin later found his way back to the U.S. and gave

testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in 1921:

I had been with the American Red Cross people at Odessa. I was there when

the Red Army took possession of Odessa. At that time I was favorably inclined

toward the Soviet Government, because I was a socialist and had been a

member of that party for 20 years. I must admit that to a certain extent I helped

to form the Soviet Government of Odessa ....39

While adding that he had been arrested as a spy by the Denikin government of South Russia,

we learn little more about Rubin. We do, however, know a great deal more about Robert

Minor, who was caught in the act and released by a mechanism reminiscent of Trotsky's release

from a Halifax prisoner-of-war camp.

EXPORTING THE REVOLUTION:

ROBERT MINOR

Bolshevik propaganda work in Germany,40 financed and organized by William Boyce

Thompson and Raymond Robins, was implemented in the field by American citizens, under the supervision of Trotsky's People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs:

One of Trotsky's earliest innovations in the Foreign Office had been to

institute a Press Bureau under Karl Radek and a Bureau of

International Revolutionary Propaganda under Boris Reinstein, among whose

assistants were John Reed and Albert Rhys Williams, and the full blast of

these power-houses was turned against the Germany army.

A German newspaper, Die Fackel (The Torch), was printed in editions of half

a million a day and sent by special train to Central Army Committees in

Minsk, Kiev, and other cities, which in turn distributed them to other points

along the front.41

Robert Minor was an operative in Reinstein's propaganda bureau. Minor's ancestors were

prominent in early American history. General Sam Houston, first president of the Republic of

Texas, was related to Minor's mother, Routez Houston. Other relatives were Mildred

Washington, aunt of George Washington, and General John Minor, campaign manager for

Thomas Jefferson. Minor's father was a Virginia lawyer who migrated to Texas. After hard

years with few clients, he became a San Antonio judge.

Robert Minor was a talented cartoonist and a socialist. He left Texas to come East. Some of his

contributions appeared in Masses, a pro-Bolshevik journal. In 1918 Minor was a cartoonist on

the staff of the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Minor left New York in March 1918 to report the

Bolshevik Revolution. While in Russia Minor joined Reinstein's Bureau of International

Revolutionary Propaganda (see diagram), along with Philip Price, correspondent of the Daily

Herald and Manchester Guardian, and Jacques Sadoul, the unofficial French ambassador and

friend of Trotsky.

Excellent data on the activities of Price, Minor, and Sadoul have survived in the form of a

Scotland Yard (London) Secret Special Report, No. 4, entitled, "The Case of Philip Price and

Robert Minor," as well as in reports in the files of the State Department, Washington, D.C.42

According to this Scotland Yard report, Philip Price was in Moscow in mid-1917, before the

Bolshevik Revolution, and admitted, "I am up to my neck in the Revolutionary movement."

Between the revolution and about the fall of 1918, Price worked with Robert Minor in the

Commissariat for Foreign Affairs.

ORGANIZATION OF FOREIGN PROPAGANDA WORK IN 1918

PEOPLE'S COMMISSARIAT FOR

FOREIGN

AFFAIRS

(Trotsky)

PRESS BUREAU

(Radek)

Field Operatives

John Reed

Louis Bryant

Albert Rhys Williams

Robert Minor

Philip Price

Jacques Sadoul

In November 1918 Minor and Price left Russia and went to Germany.43 Their propaganda

products were first used on the Russian Murman front; leaflets were dropped by Bolshevik

airplanes among British, French, and American troops — according to William Thompson's

program.44 The decision to send Sadoul, Price, and Minor to Germany was made by the

Central Executive Committee of the Communist Party. In Germany their activities came to the

notice of British, French, and American intelligence. On February 15, 1919, Lieutenant J.

Habas of the U.S. Army was sent to Düsseldorf, then under control of a Spartacist revolutionary

group; he posed as a deserter from the American army and offered his services to the

Spartacists. Habas got to know Philip Price and Robert Minor and suggested that some

pamphlets be printed for distribution among American troops. The Scotland Yard report

relates that Price and Minor had already written several pamphlets for British and American

troops, that Price had translated some of Wilhelm Liebknecht's works into English, and that

both were working on additional propaganda tracts. Habas reported that Minor and Price said

they had worked together in Siberia printing an English-language Bolshevik newspaper for

distribution by air among American and British troops.45

On June 8, 1919, Robert Minor was arrested in Paris by the French police and handed over to the American military authorities in Coblenz. Simultaneously, German Spartacists were

arrested by the British military authorities in the Cologne area. Subsequently, the Spartacists

were convicted on charges of conspiracy to cause mutiny and sedition among Allied forces.

Price was arrested but, like Minor, speedily liberated. This hasty release was noted in the State

Department: