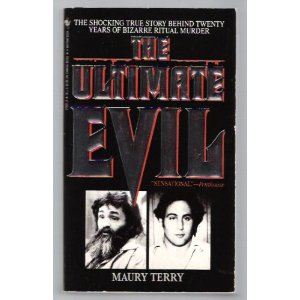

THE ULTIMATE EVIL

BY MAURY TERRY

BY MAURY TERRY

Chapter VII

An Investigation into a

Dangerous Satanic Cult

Chapter VII

Confession

It was shortly after midnight on August 11. The night was

muggy, the air conditioning faulty, and the rushing sound of

cars speeding by on the expressway near the White Plains

apartment weakly mimicked the relaxing roll of the Atlantic's

waves on Fire Island.

I was attempting to doze off to a radio talk show, and was

tuned to the talented, sandpaper personality of Bob Grant,

who was fielding questions from listeners concerned with the

Son of Sam killings.

About a week before, Grant was unnerved^by a caller who

had credibly passed himself off as the gunman. But the police,

after studying a tape of the conversation, decided it probably

was an impostor. As New Yorkers offered their theories on the

case to Grant, I was startled to full awareness when he announced

he'd just received a report that a suspect was under

arrest.

I turned on the TV in time to see Berkowitz escorted

through the crowd at One Police Plaza. At this moment, in

another part of the country—Minot, North Dakota—one John

Carr was also watching television. He'd just driven to the

small north land city from New York and was sitting in his

girlfriend's civilian apartment on the U.S. Air Force base near

Minot when a bulletin about Berkowitz's arrest flashed across

the screen.

"Oh, shit" is all he said.

Back in New York, someone else was responding to the capture.

According to Berkowitz, an individual connected to the

case and whose name neither he nor the police have revealed,

phoned Police Plaza, somehow got through to Captain Joseph

Borrelli and asked the task force supervisor if Berkowitz was

implicating anyone else in the killing spree.

"The telephone conversation bothered Borrelli. This was obvious," Berkowitz would later write. But Borrelli, perhaps

thinking of the champagne on ice, then shrugged off the incident.

The spirits may have been bubbly at the N.Y.P.D, but several

cups of warmed-over coffee were the extent of my celebrating

as I absorbed the unfolding developments through the early morning

hours. I was intrigued that Berkowitz resembled none

of the composite sketches and that he resided in my former

hometown of Yonkers. I'd heard of Pine Street, but was unable

to fix its location. After four hours of sleep, I phoned my

father at 7:30 A.M. and asked him about it. Though not in the

city, he knew the Yonkers streets better than I did.

"It's off Glenwood, down the hill, just below North Broadway.

It's a small, one-way street. You've seen it a thousand

times," he said.

"What are the other streets around there?"

"Funny you asked that. Remember last week when you were

talking about the aliases in that letter? Well, Wicker Street is

right behind Pine, running down to Warburton. That sounds

like your 'King Wicker' thing to me."

I was very interested in Pine Street itself, and even more

struck by the realization that the Breslin letter's "Wicked

King Wicker" alias apparently was a clue to the name of a

street. The information was significant because I'd been doing

a little "roadwork" of my own the preceding three days.

Since leaving Fire Island on August 1, I'd made a full-time

evening job of researching the case, having paused only on

Saturday night, the sixth, to take Lynn out to dinner at a

restaurant along the Saw Mill River Parkway in Elmsford.

Returning at midnight, I dropped her at the door before parking

behind the apartment building. The residence was but a

block from the Cross Westchester Expressway, and we were

cognizant of the killer's penchant for striking near the parkways.

Later, I'd learn that a Berkowitz letter received that same

day by Craig Glassman in Yonkers warned that "the streets of

White Plains" would run red with blood. It was another small

irony; but one I wouldn't forget.

The next morning, Sunday, August 7, the Daily News reprinted

the entire text of the June letter to Breslin. Reading it

over, I was struck by a hunch, a feeling—whatever—that the

letter contained more than met the eye.

It was the note's second P.S. that drew my attention.

Whereas the body of the letter was flawless in its "correctness"

and formal tone, these five phrases (keep 'em digging; drive on;

think positive; get off your butts; knock on coffins) were disjointed

and top-heavy with slang. They simply didn't blend

with the rest of the wording. Moreover, by inserting them into

a postscript, the killer had set them apart and called even more

attention to them, I thought. But why?

It was, I finally reasoned, quite possibly a list of five items.

As I read the P.S. again, the words "keep," "drive," "get off'

and "knock" suddenly seemed to spring off the page.

"Directions," I said out loud. "Maybe they're a set of directions.

'Go here, do that, turn off.' "

The letter's aliases were clues; so why not the P.S. as well?

Why not include a set of directions disguised in code form?

The ultimate come-and-get-me? It was widely known that the

killer was said to be taunting, daring the police to capture him.

The more I looked at the wording, the more sensible it seemed.

For the remainder of Sunday, the seventh, and for another

five hours the night of the eighth, I experimented with any

kind of system that came to mind; I even went to the library

and checked out books on World War II and other ciphers. I

added and subtracted letters to words, substituted letters and

tried dozens of combinations—none of which made any real

sense. A few times I thought I was on to it when one or two

words melded together. But then the other phrases wouldn't fit

in.

I called two friends, Bob Siegel and Ben Carucci, and asked

them to give some thought to the breakdown. Both men began

to experiment with the phrases, and I was glad they did, because

I was stumped. It had been draining work. I was still

convinced the answer was lurking, but gazing around the

apartment—with books, crumpled papers and overflowing

ashtrays everywhere—I doubted I'd ever find it.

"You're burning yourself out," Lynn warned. "Take a break

from it and clear your head."

She was right.

On the night of August 9, after a daylong respite, the waters

suddenly parted. With hindsight, it seemed ridiculously simple.

But in that simplicity lay the system's strength. I had been

looking too deep, bypassing the obvious. The solution was a

combination of two "codes"—word games, actually. One piece consisted of basic word association, a crossword puzzle type of

system. The other element was based on a ploy I'd come to

learn was a common satanist trick: spelling words backwards.

I looked at the first phrase, "keep em digging." Why, I wondered,

would the ever-careful Son of Sam, so language-conscious

throughout the letter, slip into "em" instead of using

"them"? Maybe it wasn't a slip: "em" backwards spelled

"me." The word preceding it, "keep," then became "peek"—

as in "look for" or "see." The next word, "digging," couldn't

be reversed, but using the crossword or word association approach,

it did become "home." In the United Kingdom, as the

dictionaries pointed out, a "digging" is a home (often shortened

to "digs"). The first phrase now read: LOOK FOR ME

HOME.

The next expression, "drive on," offered two possibilities.

Reversing the word "on" resulted in "no."—the abbreviation

for "north." If "drive" was left as it was, the phrase became:

DRIVE NORTH. However, using word association, a "drive"

was also a street, an avenue, a roadway or broadway. So the

phrase could have said: NORTH AVENUE (street, roadway,

etc.).

Continuing, with "think positive" word association was again the key. "Think" became "head," as in "mind," "brain," etc.; and "positive," after eliminating several other possibilities, became "right"—as in "certain," "sure," etc. The phrase read: HEAD RIGHT.

I was now looking at what I was sure was a set of directions. My failure, as I'd later learn, was not to have looked at the "Wicker" alias in the same way. But with the next expression in the P.S.—"get off your butts"—I soon saw that the only word Son of Sam had toyed with was "butts." Via word association again, "butts" became "ash"—as in cigarette butts. The reconstructed phrase said: GET OFF ASH.

Finally, through picking and choosing, "knock on coffins" translated to KNOCK ON PINE—a coffin being a "pine box."

The process, once I'd caught on to the system, went rather quickly, consuming about five hours. I sat back at the kitchen table and printed it all out at once: LOOK FOR ME HOME . . . NORTH AVENUE (street, roadway, etc.) . . . HEAD RIGHT . . . GET OFF ASH . . . KNOCK ON PINE.

At 10 P.M., I called both Siegel and Carucci. "It's got to be right; it's got to be right," I emphasized. When I explained the breakdown rationally, each man agreed the decoding made sense.

I told them I was going to check street maps of the entire metropolitan area to try to confirm the analysis and to develop a list of possible addresses. But after I hung up from the calls, my mood changed. I started doubting myself. I also began to rationalize that the N.Y.P.D, with access to coding professionals, had assuredly traveled this road before me.

Within an hour, despite encouragement from Lynn, I'd convinced myself that I was wrong about the entire matter. I also knew the police were being deluged with well-meaning tips, and saw myself being filed in the "crackpot" folder.

Now, with Berkowitz having been arrested twelve hours earlier, I studied a street map of Yonkers. I located Pine Street and backtracked across the page with my finger: North Broadway . . . Ashburton Avenue. It was all there. But rather than elation, I felt stupid. I had been familiar with all these Yonkers streets for years; yet I hadn't even thought of them in the search.

But from the map, the trail was clear: to reach David Berkowitz's apartment from any of the major routes out of New York City—site of the investigation—one would exit the parkways or thruways, drive across Ashburton Avenue, head right off Ashburton onto North Broadway and proceed to Pine. Despite what the map told me, the entire idea of a code sounded so bizarre that I wanted more assurance. But where to get it?

Once again, I was sitting close to the answer. I contacted Benoit Mandelbrot, a respected Ph.D. in mathematics, and asked him about the odds of the analysis being correct. Gunshy, I refrained from telling him the question concerned Son of Sam. Instead I simply asked about the probabilities that five phrases could, in order, lead to a particular address if the writer had not intended to incorporate such a ploy.

Mandelbrot, who had a reputation for graciousness and patience with the uninitiated, explained that the series of phrases could be likened to a mathematical progression. The odds against one phrase being accurate were small; against two being on target they increased dramatically; and so forth. Finally, the odds against all five—in order—leading step by step to the right address were almost impossible to calculate as a coincidence or an unintentional happening.

"So," Mandelbrot intoned, "it's not a coincidence. What you have done is correct. If you sent me a letter, what do you think the odds would be that I could get step-by-step directions to your house out of five successive phrases if you didn't intend to word your writing in such a manner?"

By using layman's language, Mandelbrot hit home—in more ways than one.

In the coming months, a long-term friend of Berkowitz's, Jeff Hartenberg, would tell the press: "David always liked to play word games." Berkowitz himself, in discussions with doctors and others, would state that "hidden messages" and "hints" on where Son of Sam could be found were contained in the two letters. However, he would consistently refuse to discuss the matter of who actually wrote the Breslin letter, or at least provided the wording. This subject would eventually evolve into one of the strongest pieces of conspiracy evidence. But that was in the future. On August 11,1 was left to ponder the implications of the "code."

David Berkowitz was doing precious little pondering on the eleventh of August. Instead, in the hours following his arrest, he was amazing the assistant district attorneys with his "encyclopedia" memory as he readily confessed to all the .44 shootings. He also confessed to wounding a woman in Yonkers with a rifle. The police had no record of any such incident. This development should have raised questions about the other confessions—but didn't.

"His recall appeared marvelous," Queens assistant district attorney Herb Leifer said three years later. "It was almost as if it was all scripted ahead of time; and it probably was. There were holes in his statements when they were compared to established information. The DA [Santucci of Queens] never liked it; but he didn't take the statement, and there was no access to Berkowitz afterwards for the prosecution. He was turned over to the psychiatrists. And of course Santucci had no control over Brooklyn or the Bronx," said Leifer. "So what we had was a command performance by David—and they wanted to believe everything he said anyway."

Leifer was referring to the inconsistencies and contradictions that dotted Berkowitz's confessions. Primarily, major flaws appeared in the Berkowitz version of the shootings of Robert Violante and Stacy Moskowitz in Brooklyn and the Queens attacks on Joanne Lomino and Donna DeMasi, Christine Freund and Virginia Voskerichian.

Other problem areas, including the Bronx shootings, may also have existed. But in some instances, without witnesses or other evidence to contradict Berkowitz's original statements, no one knew for certain.

In total, there were significant discrepancies in the confessions to fully half the .44 attacks—an astounding fact when one considers that the N.Y.P.D and the Bronx and Brooklyn district attorneys took no action to investigate the case after the arrest—except to clear up a handful of "loose ends," as the police put it.

The confessions will be published here for the first time; and all crucial passages will be included—especially those relating to the incidents at which contradictions appeared.

It will be possible to identify many of the inconsistencies and to see—from the slant of the questions to Berkowitz—the areas which even then were troubling the assistant district attorneys themselves.

It was shortly after 3:30 A.M., August 11. Berkowitz, who had been awake for about twenty-one hours, was nonetheless showing no signs of confusion or exhaustion, as might have been expected. A large number of detectives and assistant district attorneys had gathered in the conference room of the chief of detectives at One Police Plaza.

First up would be Ronald Aiello, head of the Brooklyn DA's homicide bureau. He would be followed by William Quinn, an assistant from the Bronx, and Martin Bracken, an assistant to Santucci in Queens. Aiello would open the session because Berkowitz was arrested by Brooklyn detectives as a result of the Moskowitz investigation. From this point, the Brooklyn DA's office would ride herd over the case.

Aiello finished his introductory querying of Berkowitz, who had waived his right to an attorney, and was now ready to ask the curly-haired postal worker about the Moskowitz-Violante shootings

Q. David, on July 31, 1977—where were you living at that time?

A. The Pine St. address.

Q. That's up in Yonkers?

A. Yes.

Q. Who were you living with?

A. Myself . . .

Q. How long had you been living there?

A. A little over a year.

Q. Do you live with anyone, David?

A. No. [Berkowitz then said he'd eaten dinner that night at a Manhattan diner and drove out toward Long Island. Aiello, very much aware of the yellow V.W saga, then asked the suspect about the type of car he drove.]

Q. What kind of car do you have?

A. 1970 Ford Galaxy.

Q. What color is it?

A. Yellow.*

* The car was actually a faded yellow, almost beige or cream-colored, t Berkowitz claimed in 1977 that his relationship with Sam Carr was only "mystical"—that he didn't actually know him. Yet even in this early post-arrest comment, he acknowledged knowing that Sam had a daughter named Wheat.

Q. How long have you had that car?

A. About three years.

Q. Is the car completely yellow?

A. No, a black vinyl roof . . .

Q. Is that a two-door or four-door?

A. Four-door.

Q. Were you using that car on the 31st?

A. Yes, I was . . .

Q. Were you with anyone, or were you alone when you were having your dinner on 10th Avenue?

A. I was alone.

Q. Where did you go from there—out to Long Island?

A. Yes. Long Island, Brooklyn.

Q. Did you have any purpose in going out on Long Island? Just to take a ride?

A. Purposely going out killing somebody.

Q. Did you have anyone in mind at that time—or anyone you might come across?

A. Whoever would just come around—when I was told who to get.

Q. Who told you who to get?

A. Sam Carr.

Q. Who is Sam Carr?

A. My master.

Q. Where does Sam live?

A. In Yonkers.

Q. Is Sam the father of Wheat Carr?

A. Yes.

Q. How long have you known Sam, approximately?

A. Probably—well, as Sam, I'd say just a little over a year; a year and a half.

Q. Is that his actual name—Sam Carr?

A. That's the name he goes by, yes.

Q. Did you have any discussion with Sam that particular day, about finding someone to kill?

A. I just had my orders.

Q. Do you want to tell me how you got those orders?

A. Yes, he told me through his dog, as he usually does. It's not really a dog. It just looks like a dog. It's not. He just gave me an idea where to go. When I got the word, I didn't know who I would go out to kill—but I would know when I saw the right people.

Q. Did you have a location in mind, David?

A. Let's just say the area I was in, Bensonhurst, was one of several I rode through . . .

Q. About what time did you reach the Bensonhurst section?

A. Two o'clock. No. Yeah. Two o'clock, about two o'clock . . .

Q. Where did you park?

A. On Bay 17th, between Shore Parkway and Cropsey Ave.

Q. Are you familiar with that neighborhood?

A. I have been there before.

Q. On what occasion were you there?

A. I'd say the past week.

Q. Prior to going there that night you were there?

A. Yes.

Q. What brought you there on that occasion?

A. I had to go and kill somebody—what can I tell you?

Q. .. . Do you recall where you parked your car exactly on the block?

A. Up by a fire hydrant, midway between Cropsey and Shore Parkway.

Q. Did you realize you parked your car by a hydrant?

A. Yes. I saw the police give me a summons.

Q. How did you see that?

A. I was walking away. I saw a police car coming up Shore Parkway and turn onto Bay 17th, going up that street. I had a feeling they would go by my car. .. . I saw the policeman give me a summons. Then, they went slowly up the block near Cropsey Avenue, and pulled over again. I watched for about ten minutes. They got out of the car. I don't know what they were doing, but I went back to my car. There was a ticket on it.

Q. What were you wearing that night?

A. Blue denim jacket, blue dungarees.*

* This is how Mrs. Davis described Berkowitz's attire, as did Mary Lyons, who saw him after the shooting.

Q. What did you have on under your denim jacket?

A. A light brown shirt.

Q. When you went back to your car . . . did you take the ticket off the windshield?

A. Yes.

Q. What did you do with it?

A. I put it inside the car.

Q. Tell me what you did from there.

A. I was still walking around the area, went back to the park, sat down for a while.

Q. Where were you sitting—on the bench?

A. Sitting on a bench.

Q. Did you have a weapon with you at that time?

A. Yes.

Q. What weapon?

A. .44 Bulldog.

Q. Then what did you do, David?

A. I saw that couple, Stacy Moskowitz and her boyfriend. They were by the swings; they went back to their car. I don't know how much time elapsed, maybe ten minutes or so. I walked up to their car . . .

Q. Were there other cars parked, or did other cars come eventually?

A. Eventually.

Q. You say you saw this Stacy Moskowitz car and then you saw the one up in front of them?

A. No, the one up front was there before.

Q. Then Stacy Moskowitz came afterwards?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you see them get out of the car?

A. No, I was too far down in the park. I saw them walking. I saw a couple by the swings. I didn't know it was them. I saw them go back to the car.*

* In a later letter to a psychiatrist, Berkowitz contradicted this statement by saying: "I saw her and her boyfriend making out in the car. Then, they walked over the walk bridge and went along the path by the water . . . and then came to where I was by the swings."

Q. Then what did you do?

A. I just—I don't know. I waited for a time. I don't know how much time elapsed. I just went up to the car. I just walked up to it, pulled out the gun and put it—you know—I stood a couple of feet from the window.

Q. Were the windows open or closed?

A. Open, and I fired. [Berkowitz then described how he "sprayed" the car with bullets.]

Q. Then what did you do?

A. I turned around and I ran out of the park through those town houses [the garden apartments where Mrs. Davis and Mary Lyons lived].

Q. You say you ran through the park. You came out of the park eventually?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you go out an exit or hole in the fence?

A. There was a hole in the fence.

Aiello now had several more problems. Berkowitz, who said he'd arrived in the neighborhood at 2 A.M., also said he knew Tommy Zaino's car was at the scene before Violante's, and at a location Berkowitz said he hadn't walked to yet. Violante had pulled into the parking spot between 1:40 and 1:45. Moreover, Berkowitz had told the police that Zaino had been the original target, but was spared when he pulled forward. This action occurred at approximately 1:35, a full twenty-five minutes before Berkowitz said he parked two blocks away.

This wasn't simply a matter of confusion regarding the time: Berkowitz said he arrived just before the police ticketed his car —an action recorded by the 2:05 time on the ticket.

Aiello was also faced with Berkowitz's saying he left the scene in a different direction from that of the man who ran through the park exit and entered the yellow VW.

Certainly concerned about the V.W chase, Aiello then asked Berkowitz how he left the area. Berkowitz confounded the issue even more by saying he drove as far north as he could on 18th Avenue, a street located east of Bay 17th. This route took him in a completely different direction from that of the V.W driver.

Aiello then concluded his questioning by asking Berkowitz about the variety of weapons he owned, and about the origin of the .44. Berkowitz said his Army pal Billy Dan Parker had purchased it for him while Berkowitz was visiting him in Houston in June 1976.

Aiello's interrogation about the most infamous homicide in New York history had lasted thirty-two minutes. He did not follow up on the obvious discrepancies in Berkowitz's account.

Berkowitz's statement that he removed the ticket from his windshield was confirmed by Mrs. Davis, who saw him do it. However, Mrs. Davis—whose account was supported by her companion, Howard Bohan—insisted that Berkowitz didn't even return to the park at that late time, 2:20, but instead left to follow the police car.

Also, at no time did Aiello ask Berkowitz to explain why, if his confession was accurate, he was back over on Bay 17th Street again at 2:33 when he passed Mrs. Davis as she walked her dog just two minutes before the shots were fired. Berkowitz, simply put, claimed to be in the park the entire time, while Mrs. Davis' account twice put him well away from the shooting site.

Beyond these and the other footnoted contradictions were, of course, the matters of the yellow V.W, the clothes the killer wore and the gunman's physical appearance and hairstyle— radically different from Berkowitz's.

"Nobody wanted to upset the applecart," Herb Leifer would later say. "They didn't want to go into any areas that might upset David or rattle him into changing his mind about confessing."

Indeed, the only "trick" question Aiello threw Berkowitz concerned the bench sitting; and Berkowitz fell for it. The actual killer, according to Violante, had been leaning against a rest-room building and not seated on a bench when the two victims walked within several feet of him—another encounter Berkowitz failed to confess to.

Berkowitz would later create still another version of the shooting that again contradicted established fact. After telling Aiello he'd simply walked up to the passenger's side of the victims' auto and fired into it, as the killer actually did, he told a psychiatrist: "I walked straight to the car. When I got to the rear of it I looked around, then stepped onto the sidewalk." (There was no sidewalk.) "I moved right to the driver's side and pulled the gun out." (Violante and Stacy were shot through the passenger's window; in fact, not a single Son of Sam victim had been fired on from the driver's side.)

Aiello, who is now a New York State Supreme Court judge, gave way to William Quinn, an assistant district attorney from the Bronx. Quinn managed to better Aiello's interrogation time record, consuming only twenty-seven minutes to question Berkowitz about three murders: those of Donna Lauria, Valentina Suriani and Alexander Esau.

There was little noteworthy information in these confessions, except that Berkowitz had Suriani and Esau seated in the wrong positions in their auto—a mistake he probably picked up from erroneous newspaper reports. He also forgot to mention that a letter had been left at that scene; but Quinn was quick to suggest the answer:

Q. Now what did you do after you fired the four shots?

A. I ran to my car and got in my car and drove off.

Q. Did you leave anything at the scene?

A. Oh, yeah, right. The letter. I had it in my pocket. It was a letter addressed to Captain Borrelli. Quinn had some concern about the Breslin letter, and a few other matters as well:

Q. Did you write a letter to Mr. Breslin?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. And you wrote it yourself?

A. Yes.

Q. Why did you mail it from New Jersey?

A. I was there at the time, hunting.

Q. Did you ever admit to anyone before tonight what you had done in relation to the Bronx cases?

A. No.

Q. To anybody at all?

A. No.

Q. . . . Did you write any other letters besides the two we mentioned?

A. Not addressed to anyone.

Q. Ever mail them?

A. No.

Q. Ever call the police?

A. No.

Q. Ever identify yourself as Son of Sam?

A. No.

In speaking to Quinn about the Suriani-Esau killings, Berkowitz had known, without prompting, that the words "Chubby Behemoth" were contained in the letter left at that scene. Since the note was not made public, Quinn had reason to be satisfied Berkowitz was involved in the shootings.

In his confession to the murder of Donna Lauria and the wounding of Jody Valente, Berkowitz stuck close to the facts of the case. Still, Quinn had some concerns:

Q. Did you have the same hair[style] as you have now?

A. Yes.

Q. You didn't have a wig?

A. No.

Q. . . . Had you followed either one of those two girls earlier in the evening—nine or nine-thirty? [This was a reference to the suspicious yellow car, smaller than Berkowitz's, cruising the area at that time.]

A. No.

Martin Bracken, an assistant district attorney from Queens, began his questioning at 4:34 A.M. by asking about the wounding of Carl Denaro as he sat on the passenger's side of Rosemary Keenan's navy blue Volkswagen, which Berkowitz incorrectly stated was "red."

He said he fired five times at the car and that he intended to kill "just the woman. I thought she was in the front seat, passenger's side. It was very dark."

There were no witnesses to this shooting. The person who pulled the trigger, however, had fired wildly—unlike the Lauria shooter. The remainder of the questioning about this attack was sketchy, and Berkowitz's answers were brief and apparently factual.

The shootings of Joanne Lomino and Donna DeMasi were another matter. It was this incident which resulted in two composite sketches of a gunman who didn't remotely resemble Berkowitz and a report from a witness that the shooter had fled carrying the weapon in his left hand. Berkowitz is right handed.

Q. Who did you fire at?

A. The two girls.

Q. And where were they seated?

A. They were standing by the porch of one of the girls' homes.

Q. . . . Did you walk up to the location where they were seated?

A. Yes.

Q. . . . Do you recall what you were wearing that night?

A. No.

Q. Do you recall the weather conditions?

A. A bit chilly, clear.

Q. And could you describe what happened when you came up to the two girls?

A. I walked up and I was going to shoot them. I tried to be calm about it and not scare them, but they were frightened of me and started to move away. And I asked them—I didn't know what to say to calm them down—so I said I was looking for an address. I'm looking for a certain address or something like that and at that time I was a few feet from them, and I pulled out the gun and opened fire.

Q. . . . What position were you in when you fired?

A. I was at maybe eight or nine feet from the steps or something.

Q. And did you go into a crouch position at that time?

A. Well, I just picked up the gun—they were like running up the steps. I stood upright.

Q. And how many times did you fire?

A. Five.

Q. And did you use both hands or one hand to hold the gun?

A. Both, I believe.

Q. And when you fired, did you hit anyone?

A. Yes. Both girls.

Q. Did you see what happened after you fired?

A. No, they just fell down.

Q. . . . When you fired the shots at the two girls, were they face to face with you or were their backs to you?

A. Face to face.

Q. And were they standing still or running?

A. They were running.

Q. In which direction were they running in relation to you?

A. Towards the door, but they were on the top and the door wouldn't open. They looked at me, facing me.

Q. Do you recall what you were wearing that day?

A. No, I don't.

Q. Did you have the same hairstyle?

A. Yes.

Q. Anything physically different about you on that day?

A. No. .

Q. And did you see anybody besides the two girls as you were getting out of your car?

A. Yes.

Q. Who?

A. An elderly woman at the porch of her house and I think she was putting on or turning off a porch light.

Q. Now, did she say anything to you at this time?

A. No.

Q. Now, did she look at you?

A. I believe she did, yes.

Q. . . . Did you ever have occasion to get out of the car prior to the first time you went to the girls?

A. Just to urinate or something.

Q. Did you get out around Hillside Avenue and 262nd [Street]?

A. No.

Q. Now, did you use the same gun that you used on the prior occasions, the one in Queens and the Bronx?

A. Yes.

Q. Now, did you use the same ammunition that you purchased in Houston?

A. Yes.

Berkowitz twice said the girls were running up the steps. However, Joanne Lomino stated to prosecutors: "We were standing by the sidewalk talking. We walked over to the porch and we were standing for about five minutes. I heard a voice, then turned around and the guy pulled a gun and started shooting at us."

She added: "I turned around and the gun was already out and he was firing." The girls weren't running anywhere.

Berkowitz also confessed that the victims were face to face with him. Joailne Lomino, struck first, was shot in the back. She further stated: "I had my back turned towards him . . . and he just had the gun out and he fired it. My back was towards him, though."

Bracken's question to Berkowitz as to whether he'd gotten out of his car at Hillside and 262nd was based on the girls' observation of a suspicious man, possibly the gunman, hiding behind a telephone pole at that location, which wasn't far from the shooting site. His question about whether or not the same .44 had been used related to the lack of ballistics evidence linking the bullets from this shooting to any others.

Berkowitz later told a psychiatrist that he "just popped out" of "the lot around the corner" before approaching the girls. There is no such lot.

Bracken, who conducted the most comprehensive of the three assistant district attorneys' interrogations, then shifted gears and began to question Berkowitz about the murder of Christine Freund as she sat in her boyfriend's car in Forest Hills on January 30, 1977.

This Berkowitz confession also went unchallenged. Later in the narrative, the in-depth follow-up investigation of the Freund murder will be explained in detail. These are among the key areas of the confession I would be analyzing:

Q. Where did you park your car?

A. I parked on a street that runs parallel to the Long Island Rail Road. It's a small winding street. I don't know the name of it.

Q. . . . And did you get out of your car at that time?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. And where did you go?

A. In the vicinity of Austin Street.

Q. . . . And can you tell me in your own words what happened?

A. Yes. I was walking in the opposite direction. I saw them walking down [from the restaurant to their car, parked in Station Plaza by the railroad station], we just passed each other, we crisscrossed. We almost touched shoulders.

Q. You passed by them?

A. Yes. They got into their car and I saw Mr. Diel get in and he reached over and opened up the door for Miss Freund and I was standing four or five feet away. And I watched them get in the car, and I guess a minute went by, and I opened fire.

Q. When you approached them, did you approach from the front or the back?

A. Back.

Q. . . . And what were you wearing on that occasion?

A. Heavy winter clothing.

Berkowitz then described how he fired three shots through the passenger's window, aiming only at Christine Freund. He said he used only three bullets, rather than four or five as in most other incidents, because "I only had one person to shoot." Later, Bracken returned to the "shoulder touching" occurrence.

Q. In relation to the car where Diel and Freund were sitting,

where did you first see them when you crisscrossed or almost

touched shoulders?

Q. In relation to the car where Diel and Freund were sitting,

where did you first see them when you crisscrossed or almost

touched shoulders?

A. 71st and Continental. [71st and Continental are the same street, with two names. Berkowitz actually meant to say Continental and Station Plaza.]

Q. And they were walking towards their car?

A. Yes.

Q. And you were where at that time?

A. I was coming from walking parallel to the railroad.

Q. I see—so they went diagonal past you. Would that be correct?

A. Yes.

Q. And where was your car parked in relation to the railroad?

A. You have those winding streets. It was in there.

The murder of Virginia Voskerichian took place less than a block from the Freund shooting at approximately 7:30 P.M. on March 8, 1977:

Q. What happened that night when you were in that area?

Q. What happened that night when you were in that area?

A. Just walked around all night.

Q. How long were you walking around?

A. Maybe an hour and a half.

Q. And then what happened?

A. I saw Miss Voskerichian, and I had to shoot her. She was coming up—we was walking in opposite directions.

Q. . . . And when you saw her, what did you do?

A. I pulled out the gun from my pocket and fired one shot into her face.

Q. And what did you do after that?

A. I turned around and ran towards my car.

Q. Do you recall what she looked like?

A. Vaguely.

Q. Could you tell us, please?

A. She had a long, pretty face. There was a shadow effect; long wavy hair.

Q. . . . Showing you this map, you see where the tennis courts are at the top. Where were you parked in relation to the tennis courts?

A. Adjacent to the tennis courts. The same street as the railroad.

Q. . . . Now after you shot her and to the point that you got to your car, did you see anyone?

A. Yes, there was an elderly man walking. I ran by him.

Q. Did you happen to see anyone jogging in the area? [This was a reference to Amy Johnson and her brother.]

A. No, I did not.

Q. . . . Did you say anything [to the elderly man]?

A. I said, "Hi, mister."

Q. . . . And what were you wearing on that occasion?

A. I think my ski jacket, dungarees.

Q. Were you wearing a hat?

A. A watch cap.

Q. And what type of a hat was that?

A. A brown watch cap. [The shooter's cap was also striped.]

Q. And was that in your duffel bag that was taken by the police today?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you remember the type of evening it was—the weather conditions?

A. Cold.

Q. . . . Can you describe what she [the victim] was wearing and doing at that time?

A. She was just walking home from school. She had on a long coat and boots. She was carrying her books.

Q. How far away from her were you when you fired?

A. About two feet.

The glaring problems with this Berkowitz version are evident. Primarily, the Police Department, after initially nominating "Ski Cap" as the killer, changed course and said Ski Cap was a witness and the Berkowitz look-alike who followed jogger Amy Johnson and her brother, Tony, was its prime target. That person—almost certainly Berkowitz, as the composite sketch illustrated—was hatless and wearing a beige raincoat—not the type of clothing Ski Cap wore.

Now, in custody, Berkowitz was trying to claim he had been Ski Cap and had indeed done the shooting. The scenario was totally confused and contradictory. Berkowitz was trying to become another individual—a person he didn't resemble, who was some three inches shorter and who was dressed differently —just as he'd done in confessing to the Brooklyn shooting.

The Police Department, which had initially done an about face on its prime suspect, now would do another one, accepting Berkowitz's version and still leaving one suspect—actually the shooter—unaccounted for.

There were other discrepancies, too. Berkowitz said he pulled the gun from his pocket; he later wrote it was in a plastic bag. He said the night was cold, when in fact it was springlike. He said he spoke the words "Hi, mister" as he ran by Ed Marlow. Marlow, however, had reported Ski Cap as saying, "Oh, Jesus." Berkowitz also confessed that Miss Voskerichian was wearing a "long coat," whereas, police reports show, the garment was actually a short jacket.

Berkowitz's statement that he was in the area for more than an hour is consistent with the reports of Amy Johnson and others, who had seen both the Berkowitz look-alike and apparently Ski Cap in the neighborhood well before the shooting. It is worth remembering that the Berkowitz look-alike had somehow managed to again appear ahead of Miss Johnson and her brother after they'd passed him the first time—and they were jogging. The scenario strongly suggests he was driven ahead of the pair and dropped off.

Berkowitz also confessed that after the shooting he ran to his car, which was parked near the railroad tracks only about a block from the shooting site. He later contradicted that account by telling a psychiatrist he was parked several blocks further west, in another direction.

Martin Bracken's final set of questions concerned the wounding of Judy Placido and Sal Lupo as they sat in a borrowed car near the Elephas discotheque. Berkowitz simply said he parked two blocks south and four blocks west of the disco, wandered around the area, saw the couple seated in the car, approached, fired and then ran back to his own auto and fled.

The troublesome areas regarding this attack involved the

"man with the mustache" and his yellow, Nova-sized car, as

well as other factors described in Chapter III. However, after

the arrest, a friend of Lupo's told the Daily News: "This guy

[Berkowitz] was definitely in Elephas five minutes before the

shooting." He added he'd seen Berkowitz speak with a young

woman, then turn around and say aloud to "a few people:

That girl is a snob.' " If this identification was correct, it seriously

compromised Berkowitz's confession to this shooting as

well.

The troublesome areas regarding this attack involved the

"man with the mustache" and his yellow, Nova-sized car, as

well as other factors described in Chapter III. However, after

the arrest, a friend of Lupo's told the Daily News: "This guy

[Berkowitz] was definitely in Elephas five minutes before the

shooting." He added he'd seen Berkowitz speak with a young

woman, then turn around and say aloud to "a few people:

That girl is a snob.' " If this identification was correct, it seriously

compromised Berkowitz's confession to this shooting as

well.

It was now 5:20 A.M., and the questioning of Berkowitz was over. Bracken had spent forty minutes interrogating the suspect about five different shootings. The "verdict" was now in, and the newspapers churning off the presses were already telling the story—as relayed by the police. Berkowitz was crazy. He acted on the orders of a barking dog who was the intermediary for Sam Carr, who was really a demon—Berkowitz's "master." Berkowitz had acted alone. The biggest case was over.

In the early morning hours, Mrs. Cacilia Davis was awakened by loud knocking on her door. "We're from the police," the voice behind it said, according to Mrs. Davis. Releasing the latch, she was greeted by Daily News reporter William Federici and a photographer. Federici's name had appeared on the byline of the "Make Mrs. Davis a Target" story that was on the newsstands at that moment.

Federici, said Mrs. Davis, had been a longtime friend of Joseph Strano—the detective from 10th Homicide who took down her account of the night of the shooting and later accompanied her on the shopping trip during which they unsuccessfully searched for a jacket identical to the one Berkowitz had worn.

Now, having obtained Mrs. Davis' name and address from some source or other, Federici was inside the comfortable, beautifully furnished Bay 17th Street apartment ready to hear the prized, confidential witness's own first-person story. Hesitant at first, but reassured since the killer was now arrested, Mrs. Davis agreed to pose for photos with her dog and to accompany Federici to the offices of the Daily News in Manhattan.

Mrs. Davis picks up the account: "I went with them. They told me Strano said it was all right to talk to them. So I told them what happened that night."

I interrupted: "Did you tell them about Berkowitz's car moving, leaving the neighborhood, blowing the horn and all that?"

"Yes," she replied. "I told Federici all about it. Strano already knew about the car. Strano knew, and then I told Federici about it."

Before the arrest, the significance of the car's leaving the area was minimal. The action occurred fifteen minutes before the shootings, and no one knew the owner of the flagged auto would turn out to be Berkowitz—the alleged killer. But the Galaxy's departure now took on a new—and very damaging —significance.

"Federici took down what I told him, and it was typed out. I looked at it, and it was just as it had happened," Mrs. Davis continued. "And then Strano came in."

According to Mrs. Davis, Detective Strano appeared at the Daily News, read the draft of her "first person" story and then suggested Mrs. Davis might be hungry. She then accompanied a female reporter "downstairs for something to eat," she said. "When we came back up, the part about him [Berkowitz] taking off the ticket and blowing the horn and all was taken out."

The next day, Friday, August 12, Mrs. Davis' story (under her byline, no less) appeared on page two of the News. There was no reference to her earlier sighting or the Galaxy's preshooting maneuvers—which of course occurred at the time Berkowitz claimed he'd been stalking his victims two blocks away in the park.

Strano also knew from his own DD-5 report that Mrs. Davis had barely entered her apartment when the shots rang out. He'd written that she heard the gunfire while unleashing the dog. If someone—as I later did—thought to measure distances and check time factors, serious questions would also arise.

In fact, in a "special" edition of the News published the morning after the arrest, a detective was quoted as saying: "She was standing on her stoop, unleashing her dog, when she heard the shots and the squeal of a horn." This account was inaccurate by about twenty seconds, but the red light was definitely flashing. Unless Berkowitz was a track star, the police had problems.

Accordingly, in Mrs. Davis' story the following day, the issue was avoided thusly: ". . . it was strange to see somebody with a [leisure] suit on in that heat. Before I went to sleep, I started reading the paper, and I heard what sounded like a long boom and then a horn." Through clever writing, the story implied that Mrs. Davis was lounging around her apartment for some time before hearing the shots; which wasn't true.

In still another article in the News that same day, on which Federici—Mrs. Davis' ghost writer—shared a byline, the story was further embellished and distorted: "He [the killer] walked away. She went home. Fifteen minutes later [emphasis added],she went to her window to turn on the air conditioning. She heard a loud bang, and then the sound of a horn blowing." This article managed to contradict the other—even though both appeared in the same newspaper on the same day with the same reporter directly involved in both versions. One said the witness heard the shots as she opened a paper (which was technically true); the other said she'd heard them while turning on her air conditioner.

The stories, through inaccuracies in one and a writing device in the other, effectively submerged the critical time-and distance factors.

What actually transpired between Federici and Strano in the city room while Mrs. Davis was downstairs isn't known for certain. Perhaps the inaccuracies were simply the result of mistakes in the writing process. But it's more likely that they weren't.

A Brooklyn assistant district attorney, Steven Wax, later confirmed that Mrs. Davis told him Berkowitz's car drove away before the shootings. Wax said he didn't hear of the incident until the day before Berkowitz pleaded guilty in May 1978—nine months later—when Mrs. Davis explained it to him.

It seems the Brooklyn DA's office hadn't bothered to interview its own witnesses during all that time—no lineups, no checking or verifying statements from Berkowitz, etc. This lack of follow-through is illustrative of the authorities' aversion to perhaps compiling information they didn't want to address concerning what lay beneath the surface of the case. The now-you-see-it, now-you-don't intense hunt for the yellow V.W is another example of this syndrome.

The fact is this: the Brooklyn district attorney's office acknowledged receiving evidence from a star witness that seriously undermined the veracity of Berkowitz's confession. This information, which went hand in hand with the yellow V.W evidence already known by the authorities, was obtained before Berkowitz pleaded guilty. But the Brooklyn DA did nothing to halt or delay that proceeding, or to mount an investigation.

When I asked Strano about this matter, he claimed that the May 1978 session was the first time he'd heard about the Ford leaving the area. I suggested to Strano that perhaps he was making this claim because, for a variety of reasons, he'd not told the DA's office about the incident immediately and had no choice but to plead ignorance in Wax's office that day.

This suggestion was denied by Strano.

Mrs. Davis simply says that Strano is not telling the truth.

When Mrs. Davis was first interviewed by me in the spring of 1979, I was accompanied by Marian Roach, an editorial employee of the New York Times, and free-lance reporter James Mitteager. Mrs. Davis' attorney was also present at the interview, as was a friend and neighbor of the witness.

Until that moment, Mrs. Davis wasn't even vaguely aware of the technical details of Berkowitz's confession—which hadn't been released publicly—and had no idea of the importance of her account, which was supported by Howard Bohan, who was also interviewed.

It was only during the course of this and subsequent meetings, when the reconstruction of the murder scene was explained to her, that Mrs. Davis came to realize her sightings effectively eliminated Berkowitz as the gunman that night.

The knowledge made her fearful; she was apprehensive of retaliation from the "real killer," as she put it. And she was also concerned that her testimony might free Berkowitz.

"He's still a killer, I don't want that to happen," she said on several occasions. She was assured the intent wasn't to free Berkowitz, but to bring his accomplices to ground if possible.

Ironically, the police's own star witness had almost destroyed their effort to depict Berkowitz as a lone, demented killer.

Meanwhile, the Brooklyn district attorney's office steadfastly refused to act. District Attorney Eugene Gold would turn a deaf ear to the mounting evidence and continue to endorse the Berkowitz-alone position.

As for Strano and Federici, one is free to arrive at an independent conclusion. Federici subsequently left the News for a job in private industry. Strano, along with twenty-four other members of the N.Y.P.D, was promoted just nine days after Berkowitz's arrest in the largest advancement ceremony in the history of the New York City Police Department.

Down and out in March, the N.Y.P.D was now basking in the glow of its success in the Son of Sam case. Its status was restored; its rating was sky high in the public mind. And the promotion ceremony topped it off.

In coming months, a split would develop within the previously united legions of 10th Homicide. Some detectives, including Strano and John Falotico, became somewhat concerned as Detective Ed Zigo—who was attempting to obtain a search warrant at the time of the capture—sought to claim a considerable amount of undeserved credit and fame.

This knowledge is firsthand, as I spoke with Strano and others, including Zigo, on several occasions during this period. Zigo was moving in his own direction, but in conversations with others, subtle questions and hints concerning books and movies invariably were present. Mrs. Davis also said that a fight had erupted between members of the opposing camps at an awards function in Brooklyn, at which she was present.

Zigo, who may or may not have landed any blows at this alleged "Policemen's Brawl," did beat the others to another punch at least. After retiring several years later, he collaborated on a supposedly factual TV movie about the case with producer Sonny Grosso, himself an ex-member of the N.Y.P.D. The film, which first aired on CBS in October 1985, was titled Out of the Darkness. But rather than shedding any new light, the movie distorted and fictionalized the investigation, the events surrounding the arrest and Zigo's role in each.

CBS wasn't the only victim of a whitewash. In 1981, author Lawrence Klausner published a book which purported to tell the "true" story—which of course meant that Berkowitz was a salivating, demon-haunted madman who acted alone. Klausner was fed a large plateful of distortions by a handful of task force supervisors and others—all of which he dutifully digested and reported as fact. He literally canonized Captain Joseph Borrelli, Sergeant Joe Coffey and other Omega task force members, whose investigation was, despite Klausner's platitudes, an expensive failure.

But these subplots were beyond my vision of the future on August 11, 1977—the day after the arrest. I was in White Plains, holding clues from the Breslin letter I suspected were beyond Berkowitz's ability to concoct, based on background information that had already surfaced.

I was also troubled that he didn't remotely resemble some of the composite sketches of the killer and that reports I'd read of the Moskowitz murder and Mrs. Davis' role seemed contradictory.

Following that trail, I'd looked up all the "Carr" listings in the telephone book and learned, to my considerable interest, that a number for a "John Wheat Carr" existed at Sam Carr's address. John Wheat and the "John 'Wheaties'" alias in the Breslin letter—the discovery was intriguing.

In an older directory, I noticed another listing—that of a Carr III Studio. That heightened my interest because the Breslin letter was said to have been printed in the style of an illustrator or cartoonist.

The first seeds of the conspiracy investigation were now planted. There was no way of knowing that official hindrances and roadblocks would result in a long growing season.

Upstairs in a small cell in the prison ward, a heavily guarded Berkowitz paced the floor. In another wing of the hospital, Robert Violante lay quietly, still recovering from his blinding head wound.

It was now Friday, August 12, and a forty-eight-hour immersion in the media left me resigned to the belief that there would be a difficult, if not impossible, mountain to scale if I sought to resolve any questions about Berkowitz's sole guilt. But I was determined to give it a try.

After compiling the initial information about the Carr household, I followed a hunch about the "John 'Wheaties'" alias and phoned around to find someone who knew the family. Since I'd grown up in Yonkers, I was able to obtain referrals, and after about five calls I located a contact who was acquainted with them.

The conversation was revealing. By the time it ended, my adrenaline was working overtime.

"You're right, it's more than a phone listing. John Carr's nickname was Wheaties," I was told.

The contact, whom I will call Jack, added: "The nickname may have originated with the listing, which was probably a number for both John and Wheat when they were kids. Old man Sam runs an answering service, so there's lots of lines into that house. They probably just never changed it in the book," Jack suggested.

"Based on what you're telling me, John Carr was an alias of Son of Sam," I said slowly. "That's heavy stuff."

"Well, his nickname was Wheaties," Jack replied.

"But how could Berkowitz, if he wrote that Breslin letter, know John Carr's nickname if he didn't know the Carrs?" I asked. "He says he didn't; they say he didn't, and he's supposed to be this loner with no friends anywhere. He's only in that neighborhood since last year, not all his life. And he's the original Herman's Hermit. So how does he know the nickname of someone he doesn't even know?"

Jack added some more fuel: "John doesn't even live in New York anymore. He's back and forth a lot but he's been in the Air Force for years. He's somewhere in the Dakotas last I heard."

"That's even more curious. Now he knows the nickname of a guy who's only around here sporadically. . . . What do you know about this Carr studio in that house?"

"Nothing, but I'd guess that's Michael. He's some sort of a designer, I think."

Jack knew little else, except that John was about thirty and Michael "about five years younger. .. . I think you're raising some interesting questions, but Berkowitz says he was alone, and so do the cops."

"I know. I don't know where this is leading, if anywhere. But they do have him convicted already. I've been reading the papers."

Indeed, I'd been absorbing every detail I could in the aftermath of the arrest. Pages and pages of newspaper reports and countless minutes of television and radio time had successfully transmitted the official message to the nation: "Crazy David Berkowitz heard a barking dog and killed for his master, Sam."

There were many myths published about Berkowitz in the weeks following his apprehension. For instance, it was widely reported that the arrest halted him as he prepared to drive to the Hamptons to shoot up a discotheque with his semiautomatic rifle and "go out in a blaze of glory."

This story was leaked by police officials and immediately bannered in hundreds of headlines. It was false. Berkowitz said he'd driven to the Hampton's the weekend before his capture,thought about shooting up a disco, but changed his mind. But the inaccurate story, which did have a grain of truth in it, served a purpose: the N.Y.P.D had, in the nick of time, saved many lives.

Another item which received widespread publicity held that Berkowitz apparently shot and killed a barking dog behind an apartment building where he lived in the Bronx in 1975. This wasn't true either, according to building superintendent James Lynch, who knew Berkowitz at that time.

Lynch would tell me in 1984 that a neighbor actually shot the dog—his own dog, at that—in a drunken rage one night.

Another false story seeping from that same Barnes Avenue address also garnered extensive attention. It involved some "threatening notes" Berkowitz supposedly slid under the door of an elderly woman because she played her television too loudly.

Once again, Lynch told me otherwise: "I saw those notes. The woman—she's dead now—showed them to me. She didn't know who wrote them, and neither did anyone else. But if it was Berkowitz, there was nothing threatening about them at all. They were simply polite requests to please try to lower the sound."

Small matters? Not really. These are but three examples of many which, put together, painted a distorted picture of Berkowitz that made later efforts to uncover the truth even more difficult than it already was. First impressions linger, and in the Berkowitz investigation, reversing them was akin to plowing through a brick wall. The story of the loud television, for instance, appeared in hundreds of newspapers and was included in Newsweek's cover story of the arrest.

So, who was David Berkowitz? He was born in Brooklyn on June 1, 1953, and given up for adoption shortly afterwards. His mother's name was Betty Broder, a Brooklyn resident of the Jewish faith. She had been married years earlier to a man named Tony Falco, who left her. Some time later, Betty Broder began a long-term affair with a married Long Island businessman named Joseph Klineman, also of the Jewish faith. Klineman, who died of cancer in the early 1970's, never left his wife for Betty Broder Falco—but that didn't impede him from fathering Richard David.

Betty, however, already had a daughter, Roslyn, from her marriage to Falco. She couldn't keep her infant son without the willing support of Klineman, who apparently demurred. And so the baby was put up for adoption.

The media reported Berkowitz was half Italian and half Jewish because Tony Falco was listed as the father on the adoption papers. Betty put Falco's name on the document because she knew she couldn't use the married Klineman's name.

So the child was actually 100 percent Jewish, and was then welcomed into the modest Bronx apartment of Nathan and Pearl Berkowitz, a childless, middle-class couple who lived on Stratford Avenue in the Soundview section.

The baby was renamed David Richard Berkowitz. His new father, Nat, owned a hardware store on the Bronx's Melrose Avenue and worked long hours to maintain his business. He was serious about his faith, and young David received religious training, was bar mitzvahed and led a basically normal childhood.

David possessed above-average intelligence, and was capable of doing well in school when he applied himself. He enjoyed sports, particularly baseball, and cultivated a small circle of childhood friends.

In October 1967—when he was fourteen—his adoptive mother, Pearl, died of cancer. David loved her deeply, and was hurt greatly by the loss. Thereafter, his relationship with Nat, while cordial, was occasionally strained due to the father's child-rearing attitudes and David's reactions to them.

In late 1969, David and Nat moved from Stratford Avenue to a new home in the Bronx's Co-Op City, a huge high-rise complex in the eastern area of the borough. There, David, who was attending Christopher Columbus High School, accumulated a new group of friends. Prominent among them were four boys his age, some of whom he maintained contact with until his arrest.

Berkowitz liked uniforms, joining the auxiliary police at the 45th Precinct in the Bronx in 1970, while still in high school. He was also instrumental in the formation of an unofficial volunteer fire department at Co-Op City.

By his own admission, his teenage love life left something to be desired. He professed to like girls, and said he'd had a few dates, but no relationships, with the exception of one with a girl named Iris Gerhardt. Berkowitz implied the affair was significant, and it apparently was to him. Iris viewed it as a basically platonic friendship. She reported liking David as a person; and Berkowitz kept in touch with her throughout the early 1970's, writing her frequently after he joined the Army.

David graduated from high school in 1971, a few months after his father remarried. David resented the intrusion of his new stepmother, Julia, who had children of her own. One daughter, Ann*, had an influence on David's life that, if his story is correct, is shadowed with dark overtones. Berkowitz later wrote that Ann was very interested in the occult. He called her "a witch."

But with Julia in his life as an unwelcome stepmother, the Army suddenly appeared attractive to David. Nat thought his son should attend college, but David opted for the military and enlisted in June 1971, shortly after his high school graduation.

David's soldiering career was unremarkable. He was not sent to Vietnam, but did spend a year in Korea. He was later stationed at Fort Knox, Kentucky, before being discharged in June 1974.

While in the service, he received routine firearms training, achieving a mid-level competency grade as a marksman, and was brought up on minor disciplinary charges twice. While in Korea, Berkowitz said, he experimented with LSD on several occasions, as did many of his fellow G.I's. The Army did change Berkowitz in one major respect. He went in a hawk but came out an anti-military dove.

But it was during his period at Fort Knox, beginning in January 1973, that a symptom of the mind-set which would later leave him susceptible to untoward influences became manifest. Berkowitz, born and raised a Jew, began to attend Beth Haven Baptist Church in Louisville.

He said he enrolled in every program, and often remained in the church for the entire day on Sundays. He listened to religious broadcasts incessantly, studied numerous liturgical writings and began to try to convert his fellow soldiers and some of Kentucky's civilian population from a street-corner pulpit.

This was "fire and brimstone" old-time religion, and when David returned to the Bronx after his discharge in the late spring of 1974, Nat Berkowitz reached for his tranquilizers. His Jewish son was sounding as if he'd just strolled out of a cobwebbed chapter of The Scarlet Letter.

Naturally, David's new beliefs led to some difficulties with Nat. On top of that, David's inner feelings of resentment toward Julia intensified. He needed a place of his own. So, with Nat's help, he located the apartment at 2161 Barnes Avenue and moved there in late 1974, bringing along a fair amount of furniture Nat gave him.

David enrolled at Bronx Community College, and was hired as a guard by IBI Security, working in Manhattan. He also resumed contact with his friends from Co-Op City, several of whom professed to have been "put off' by his religious proselytizing.

Early in 1975, Nat Berkowitz retired from his hardware business, and he and Julia retreated to a condominium in Boynton Beach, Florida. Ann, Julia's daughter, apparently drifted off to California and became involved with a commune.

David, who had philosophically separated from his father months before, was now physically distanced from him as well. The pressure cooker was simmering.

The recipe's final seasoning was added in May 1975. David, feeling terribly alone and without purpose, begin a search for his real parents. He joined ALMA (Adoptees Liberty Movement Association), attended several meetings and then began his quest in earnest.

His "David Berkowitz" birth certificate led him to the Bureau of Records in New York City, where he discovered his real name was Richard Falco. He then called all the Falcos in the Brooklyn directory, and came up empty. An ALMA counselor subsequently steered him to the New York Public Library's collection of old telephone books. He found a "Betty Falco" in the 1965 Brooklyn edition and learned she was still at the address, albeit with an unlisted number. Berkowitz still wasn't sure this Betty Falco was his mother, but he decided to chance it.

On Mother's Day 1975 he stuck a card in her mailbox. It said: "You were my mother in a very special way." He signed it "R.F.," for Richard Falco, and wrote his phone number on the card.

He drove back to the Bronx nervous, apprehensive and yet excited at the possibility that he'd at last discover who he really was and be united with the woman who'd brought him into the world. Since the death of his adoptive mother, Pearl, in 1967, there was a well's worth of emptiness in David; a hollow pit he was desperate to fill.

Several days later Betty Falco called, and mother and son soon met for the first time since David's infancy. Berkowitz, edgy but hopeful, was ultimately crushed. He learned he was illegitimate, discovered Betty had a daughter, Roslyn, she'd not given up and absorbed other details about his heritage and Betty that further dismayed him.

He never voiced his torment, however. He instead sought to begin and maintain a relationship with Betty, Roslyn, Roslyn's husband, Leo, and their young daughters—whom David genuinely adored. He attempted to live a normal life.

But the hurts had piled too high. The lid was ready to blow off the now boiling pressure cooker.

About nine months later, in February 1976, Berkowitz inexplicably moved from the Bronx to the private home of the Cassara family in New Rochelle. Superintendent Lynch told me Berkowitz was "in the middle of a lease" when he left Barnes Avenue. He was also still working in New York City for I.B.I Security, and his Bronx rent was lower than that in New Rochelle.

So, on the surface, the move made no sense in terms of reducing his commute or any other reason usually associated with a relocation. The Cassaras would tell me they only advertised the room in the Westchester newspapers, and Berkowitz never revealed how he came to know about the rental.

Regardless, Berkowitz was out of the Cassara house just two months later. Much media noise was made of the belief that he suddenly fled the residence because of his aversion to the Cassaras' barking German shepherd dog.

Berkowitz may not have appreciated the animal, but he hadn't "fled." Records show that he applied for an apartment at 35 Pine Street in Yonkers a month before his move. His application was approved and he moved into apartment 7-E in mid-April. And so another widely reported Berkowitz myth now dies.

If Berkowitz's move to New Rochelle was mysterious, at first glance his journey to Yonkers seemed even more curious. This relocation didn't ease his commute either. Pine Street was also off the beaten track, and as such wouldn't be known to a boy from the east Bronx who most recently lived on the opposite side of Westchester County in New Rochelle.

Logically, however, Berkowitz certainly must have had some reason for choosing to live in that northwest Yonkers apartment—where the rent was also about forty dollars a month more than he was paying in New Rochelle and nearly a hundred dollars higher than his cost in the Bronx.

That reason would concern me for quite some time. I had my suspicions, but wouldn't be able to confirm them for several years.

In May, incidents of violence erupted in Berkowitz's neighborhood, as detailed in Chapter VI. There is no question that Berkowitz was involved in these crimes—but not as a sole instigator or perpetrator.

In June, just two months after arriving at 35 Pine, Berkowitz visited his father in Boynton Beach, Florida, and then drove on to Houston, Texas, where Billy Dan Parker, his Army buddy, purchased a .44 Bulldog revolver for him at a local shop. Six weeks later, the Son of Sam shootings began.

Berkowitz also found new employment in the summer of 1976 as a cabdriver in the Bronx, and later as a sheet-metal apprentice in Westchester.

In March 1977, Berkowitz joined the U.S. Postal Service, having passed the required civil service exam a year earlier. He worked in a large postal facility on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. His hours encompassed the second shift, from approximately 3:30 P.M. to midnight. It was his last job.

The New York Post, a recent acquisition of Australian publishing magnate Rupert Murdoch, was heavily involved in coverage of the Son of Sam case. At times, it was guilty of sensationalism, but so were the rest of the media. The Post was losing money when Murdoch took the reins, and he immediately laid claim to the .44-caliber investigation, engaging the Daily News, particularly, in a battle of headlines as the probe continued. It was said in New York that Murdoch "hung his hat on Son of Sam."

Two weeks after Berkowitz's arrest, I sat in the office of Peter Michelmore, the Post's metropolitan editor, and elicited his interest in the subject of John Wheaties Carr and the Carr illustration studio. The Post was headquartered at 210 South Street, near the Seaport, not far from the Brooklyn Bridge. Its city room reflected the paper's financial struggles, which antiquated typewriters and general disarray in evidence.

Murdoch had imported a number of Australian writers and editors to work at the Post; people he knew well from his overseas operations. Michelmore, a distinguished-looking, gray-haired man of about fifty, was one of those.

"I think this John Carr thing is good stuff," he said, after I explained what I'd discovered. Michelmore summoned columnist Steve Dunleavy, another Australian, and assigned him to work with me to develop the story. Dunleavy was about forty and had just written Elvis, What Happened?, which would become a best seller. Elvis Presley had just died, and Dunleavy was fortuitously working on the book with a couple of the King's ex-bodyguards at the time.

Dunleavy decided to visit my apartment in White Plains, where we discussed the case at length.

"We're going to have a hell of a time with the cops, mate," he warned. "They're not going to like this stuff at all."

Dunleavy said that he knocked on Sam Carr's door the morning after the arrest. "He had a gun underneath a towel and he pointed it right at me. I almost dropped dead on the spot. The cops say there are guns all over that house."

I showed Dunleavy the breakdown of the P.S. in the Breslin letter. We agreed it was on target, but also concurred that its publication would open the door to charges of speculative reporting, which neither of us wanted to endure.

"The cops will deny this. We need more about John Carr first. Do you know where he is?" Dunleavy asked.

"No. He's just supposed to be somewhere in North Dakota."

The meeting ended with an agreement to pursue John Carr. Dunleavy would check his sources in the city; I'd do what I could in Westchester.

A week later I heard from Peter Michelmore, who asked me to drive to his office for another session. "I think we can get something on Carr," he said.

"How?"

"We've got a man in the hospital."

"In Kings County? You've got access to Berkowitz?"

"Yes," Michelmore answered, but he didn't reveal who it was. I knew Berkowitz was being guarded closely, segregated from other prisoners and patients.

"It's got to be a doctor or a guard or someone like that," I said. "That's fantastic. Maybe we can get somewhere."

There was an ironic justice in this development. The police no longer had access to Berkowitz while I, an outsider, suddenly did—indirectly at least.

But there was no time for self-congratulation. Michelmore asked for a list of pertinent questions which the source could put to Berkowitz one or two at a time. Dunleavy, meanwhile,would use some of my information in a letter he was composing to the alleged .44-Caliber Killer. It was agreed that John Carr wouldn't be mentioned in the note: we wanted the hospital source to handle that one personally, so he could observe Berkowitz's immediate reaction.

I liked Dunleavy and Michelmore. Michelmore was low keyed and professional; Dunleavy was hell on wheels. He was bright and incisive. My only difficulty was in trying to slow him down. Sometimes, it seemed as if Steve's attention span could be measured in nanoseconds. He was also occasionally prone to a "headline mentality"—an inclination to view everything as it would appear in 72-point type on page one. He, on the other hand, believed I was too methodical, and too willing to consider fragmented data as relevant to the investigation. Our contrasting traits managed to mesh, however, and we developed a healthy respect for each other.

The Village Voice, a Murdoch weekly in New York that was often critical of the Post, once referred to Dunleavy as "Son of Steve." I jumped on that label, and took to using it in our conversations.

Within three days of this second meeting at the Post, I sent a list of questions to Michelmore. Primary subjects were the Son of Sam letters, John Carr and Berkowitz's movements at the Moskowitz-Violante shootings.

"He was supposed to be in the park," I explained to Michelmore. "So what was he doing on Bay 17th Street just before the shots rang out?"

The contradiction was news to Michelmore, but I was driving a few of my neighbors crazy with that same question. Several nights, after dinner, I'd relaxed outside my apartment with them. Invariably, the case was discussed. Usually I'd draw a map in the dirt, showing Berkowitz in the park and Berkowitz on the street at the same time. "It's impossible. Something's wrong; very wrong," I'd say.

Tom Bartley, a news editor for the Gannett Westchester Rockland Newspapers, became "Doubting Thomas" Bartley. "You must have read [the Times] wrong; there's no way he didn't do it," he'd say over and over, night after night. Bartley's attitude bothered me. Healthy skepticism was one thing, but his demeanor was one of "Don't confuse me with any facts." As he was a journalist, I thought his reactions might have been more inquisitive than they were.

Time and again I'd enunciate the discrepancies, but I couldn't reach him. "Sooner or later this thing's going to blow apart and you and Gannett are going to look foolish," I finally said after two weeks of futility elapsed. "Berkowitz lives in your circulation area and nobody up here wants to investigate this."

Bartley always had an answer. "You haven't shown me anything that's not just some coincidence," he'd say, pointing at me with the twig I'd been using to outline the Moskowitz scene on the ground. After a while, my ire would mount and heated debates would erupt.

"He enjoys busting your chops," another neighbor cut in one night. "Don't fall for it. He doesn't know what the hell he's talking about."

At that moment, the neighbor's dog flopped down on the map.

"That does it," I shouted. "It's a sign from a goddamned demon dog. Berkowitz and his dogs, and now yours." I laughed. "I give up! He did it alone!"

Bartley roared. "At least he didn't dump on it—he could have, for all it's worth!"

"We'll see, you mule-headed bastard," I replied. "We'll see." Tension broken, we switched to something we all agreed on: the lousy season the football Giants were certain to have.

Bartley, for all his bravado, underwent a slow conversion. Within a year he'd become a staunch ally and would later share a byline with me on a series on the case published by Gannett. But until that time, he plied me with regular doses of frustration.

Drawing maps in the dirt wasn't the only crawling around I did while waiting to hear from the Post contact at Kings County. Satisfied that vital clues were hidden in the Breslin letter, I obtained a copy of the unpublished Borrelli note from Michelmore and began to apply the same crossword, word association system to that communication.

A copy of the book The Story of the Woodlawn Cemetery was recovered by police in Berkowitz's apartment. Woodlawn, located in the northeast Bronx, was a beautiful, sprawling burial ground landscaped with thousands of trees, running brooks, winding roads and a swan-populated lake.

In studying the Borrelli letter, I thought some of its phrases might have hinted at specific grave sites in Woodlawn. Since Berkowitz had the book, it was possible something might be hidden at one of them.